CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CLOSING THE REAL ESTATE TRANSACTION

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

When you've finished reading this Chapter, you should be able to:

► identify the issues of particular interest to the buyer and the seller as a real estate transaction closes.

► describe the steps involved in preparing a closing statement.

► explain the general rules for prorating.

► distinguish the procedures involved in face-to-face closings from those in escrow closings.

► define the following terms: accrued items; closing; closing statement; controlled business arrangement (CBA); credit; debit; escrow account; escrow closing; Good Faith Estimate (GFE); impound account; Mortgage Disclosure Improvement Act (MDIA); prepaid items; prorations; Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA); survey; and Uniform Settlement Statement (HUD-1).

REAL ESTATE PRACTICE & PRINCIPLES KEY WORD MATCH QUIZ

--- CLICK HERE ---

I would encourage you to take this “Match quiz” now as a pre-chapter challenge to see how many of these key words or phrases you are familiar with. At the end of each chapter I recommend that you take the quiz again to reinforce these important keywords. Each page contains four words or phrases and you need to drag and drop the correct definition into the puzzle key. Each page is considered as a question, but there is no scoring and you can return to each chapter quiz as many times as needed to reinforce your memory.

WHY LEARN ABOUT... CLOSING THE REAL ESTATE TRANSACTION?

Everything a real estate licensee does in the course of a real estate transaction, from soliciting clients to presenting offers and coordinating inspections, leads to one final event: closing. Closing is the consummation of the real estate transaction. It is the time when the title to the real estate is transferred in exchange for payment of the purchase price. Closing marks the end of any real estate transaction; it is the goal toward which all the agent's efforts are driven. It's also a complicated time: Up until closing preparations begin, the agent's relationship has been primarily with the buyer or seller. During the closing period, new players come on the scene: appraisers, inspectors, loan officers, insurance agents, and lawyers. Negotiations continue, sometimes right up until the property is finally transferred, and the risk of a deal failing is high. For those reasons alone, it is vital that you understand how closings work—to ensure that they do.

PRECLOSING PROCEDURES

Closing actually involves two events: First, the promises made in the sales contract are fulfilled; second, the mortgage loan funds (if any) are distributed to the buyer. Before the property changes hands, however, important issues must be resolved, and both the buyer and the seller have specific issues to deal with.

Buyer's Issues

The buyer will want to be sure that the seller delivers title. The buyer also should ensure that the property is in the promised condition. This involves inspecting

► the title evidence;

► the seller's deed;

► any documents demonstrating the removal of undesired liens and encumbrances;

► the survey;

► the results of any required inspections, such as termite or structural inspections, or required repairs; and

► any leases if tenants reside on the premises.

IN PRACTICE One of the first efforts to put the NAR/HUD Homebuyer Protection Initiative into action is the Consumer Notice form that explains the difference between the appraisal and a home inspection and that emphasizes the importance of an inspection to protect buyers. The one-page notice must be signed on or before closing in all transactions in which an FHA-insured mortgage is involved.

Final property inspection.

Shortly before the closing takes place, the buyer usually makes a final inspection of the property with the broker (often called the walk-through). The right to have a final property inspection is normally created in the real estate sales contract. Through this inspection, the buyer makes sure that necessary repairs have been made, that the property has been well maintained, that all fixtures are in place, and that there has been no unauthorized removal or alteration of any part of the improvements.

Survey.

A survey gives information about the exact location and size of the property. The sales contract specifies who will pay for the survey. It is usual for the survey to "spot" the location of all buildings, driveways, fences, and other improvements located primarily on the premises being purchased. Any improvements located on adjoining property that may encroach on the premises being bought will also be noted. The survey should set out, in full, any existing easements and encroachments. Whether or not the sales contract calls for a survey, lenders frequently require one.

IN PRACTICE A buyer should make sure that the survey is accurate so that property purchased is exactly what the buyer wanted. Relying on old surveys is not necessarily a good idea; the property should be resurveyed prior to closing by a competent surveyor, whether or not the title company or lender requires it.

Seller's Issues

Obviously, the seller's main interest is in receiving payment for the property. He or she will want to be sure that the buyer has obtained the necessary financing and has sufficient funds to complete the sale. The seller also will want to be certain that he or she has complied with all the buyer's requirements so the transaction will be completed.

Both parties will want to inspect the closing statement to make sure that all monies involved in the transaction have been accounted for properly. The parties may be accompanied by their attorneys or their real estate agents.

Title Procedures

Both the buyer and the buyer's lender will want assurance that the seller's title complies with the requirements of the real estate sales contract. Though the practice varies from state to state, the seller is usually required to produce a current abstract of title or title commitment from the title insurance company. When an abstract of title is used, the purchaser's attorney examines it and issues an opinion of title. This opinion, like the title commitment, is a statement of the status of the seller's title. It discloses all liens, encumbrances, easements, conditions, or restrictions that appear on the record and to which the seller's title is subject.

On the date when the sale is actually completed (the date of delivery of the deed), the buyer has a title commitment or an abstract that was issued several days or weeks before the closing. For this reason, there are sometimes two searches of the public records. The first shows the status of the seller's title on the date of the first search. Usually, the seller pays for this search. The second search, known as a bring down, is made after the closing and generally paid for by the purchaser. The abstract should be reviewed before closing to resolve any problems that might cause delays or threaten the transaction.

As part of this later search, the seller may be required to execute an affidavit of title. This is a sworn statement in which the seller assures the title insurance company (and the buyer) that there have been no judgments, bankruptcies, or divorces involving the seller since the date of the title examination. The affidavit promises that no unrecorded deeds or contracts have been made, no repairs or improvements have gone unpaid, and no defects in the title have arisen that the seller knows of. The seller also affirms that he or she is in possession of the premises. In some areas, this form is required before the title insurance company will issue an owner's policy to the buyer. The affidavit gives the title insurance company the right to sue the seller if his or her statements in the affidavit are incorrect.

When the purchaser pays cash or obtains a new loan to purchase the property, the seller's existing loan is paid in full and satisfied on record. The exact amount required to pay the existing loan is provided in a current payoff statement from the lender, effective on the date of closing. This payoff statement notes the unpaid amount of principal, the interest due through the date of payment, the fee for issuing the certificate of satisfaction or release deed, credits (if any) for tax and insurance reserves, and the amount of any prepayment penalties. The same procedure is followed for any other liens that must be released before the buyer takes title.

In a transaction in which the buyer assumes the seller's existing mortgage loan, the buyer will want to know the exact balance of the loan as of the closing date. In some areas, it is customary for the buyer to obtain a mortgage reduction certificate from the lender that certifies the amount owed on the mortgage loan, the interest rate and the last interest payment made.

In some areas, real estate sales transactions are customarily closed through an escrow (discussed below). In these areas, the escrow instructions usually provide for an extended coverage policy to be issued to the buyer as of the date of closing. The seller has no need to execute an affidavit of title.

IN PRACTICE Licensees often assist in preclosing arrangements as part of their service to customers. In some states, licensees are required to advise the parties of the approximate expenses involved in closing when a real estate sales contract is signed. In other states, it is the licensees' statutory duty to coordinate and supervise closing activities.

CONDUCTING THE CLOSING

Closing is known by many names. For instance, in some areas closing is called settlement and transfer. In other parts of the country, the parties to the transaction sit around a single table and exchange copies of documents, a process known as passing papers. ("We passed papers on the new house Wednesday morning.") In still other regions, the buyer and seller may never meet at all; the paperwork is handled by an escrow agent. This process is known as closing escrow. ("We'll close escrow on our house next week.") Whether the closing occurs face to face or through escrow, the main concerns are that the buyer receives marketable title, the seller receives the purchase price, and certain other items are adjusted properly between the two.

Face-to-Face Closing

A face-to-face closing involves the resolution of two issues. First, the promises made in the real estate sales contract are fulfilled. Second, the buyer's loan is finalized, and the mortgage lender disburses the loan funds. The difference between a face-to-face closing and an escrow closing is that in a face-to-face closing, these two issues are resolved during a single meeting of all the parties and their attorneys. As discussed earlier, the parties in an escrow closing may never meet. The phrase passing papers vividly describes a face-to-face closing.

Face-to-face closings may be held at a number of locations, including the office of the title company, the lending institution, one of the parties' attorneys, the broker, the county recorder, or the escrow company. Those attending a closing may include

► the buyer;

► the seller;

► the real estate salespersons or brokers (both the buyer's and the seller's agents);

► the seller's and the buyer's attorneys;

► representatives of the lending institutions involved with the buyer's new mortgage loan, the buyer's assumption of the seller's existing loan, or the seller's payoff of an existing loan; and

► a representative of the title insurance company.

Closing agent or closing officer. One person usually conducts the proceedings at a closing and calculates the division of income and expenses between the parties (called settlement). In some areas, real estate brokers preside. In others, the closing agent is the buyer's or seller's attorney, a representative of the lender, or a representative of the title company. Some title companies and law firms employ paralegal assistants who conduct closings for their firms.

Preparation for closing involves ordering and reviewing an array of documents, such as the title insurance policy or title certificate, surveys, property insurance policies, and other items. Arrangements must be made with the parties for the time and place of closing. Closing statements and other documents must be prepared.

The exchange.

When the parties are satisfied that everything is in order, the exchange is made. All pertinent documents are then recorded in the correct order to ensure continuity of title. For instance, if the seller pays off an existing loan and the buyer obtains a new loan, the seller's satisfaction of mortgage must be recorded before the seller's deed to the buyer. The buyer's new mortgage or deed of trust must then be recorded after the deed because the buyer cannot pledge the property as security for the loan until he or she owns it.

Closing in Escrow

An escrow is a method of closing in which a disinterested third party is authorized to act as escrow agent and to coordinate the closing activities. The escrow agent also may be called the escrow holder. The escrow agent may be an attorney, a title company, a trust company, an escrow company, or the escrow department of a lending institution. Many real estate firms offer escrow services. However, a broker cannot be a disinterested party in a transaction from which he or she expects to collect a commission. Because the escrow agent is placed in a position of great trust, many states have laws regulating escrow agents and limiting who may serve in this capacity. Although a few states do not permit certain transactions to be closed in escrow, escrow closings are used to some extent in most states.

Escrow procedure.

When a transaction will close in escrow, the buyer and seller execute escrow instructions to the escrow agent after the sales contract is signed. One of the parties selects an escrow agent. Which party selects the agent is determined either by negotiation or by state law. Once the contract is signed, the broker turns over the earnest money to the escrow agent, who deposits it in a special trust, or escrow, account.

Buyer and seller deposit all pertinent documents and other items with the escrow agent before the specified date of closing.

The seller usually deposits

► the deed conveying the property to the buyer;

► title evidence (abstract and attorney's opinion, certificate of title, title insurance, or Torrens certificate);

► existing hazard insurance policies;

► a letter or mortgage reduction certificate from the lender stating the exact principal remaining (if the buyer assumes the seller's loan);

► affidavits of title (if required);

► a payoff statement (if the seller's loan is to be paid off); and

► other instruments or documents necessary to clear the title or to complete the transaction.

The buyer deposits

► the balance of the cash needed to complete the purchase, usually in the form of a certified check;

► loan documents (if the buyer secures a new loan);

► proof of hazard insurance, including (where required) flood insurance; and

► other necessary documents, such as inspection reports required by the lender.

The escrow agent has the authority to examine the title evidence. When marketable title is shown in the name of the buyer and all other conditions of the escrow agreement have been met, the agent is authorized to disburse the purchase price to the seller, minus all charges and expenses. The agent then records the deed and mortgage or deed of trust (if a new loan has been obtained by the purchaser).

If the escrow agent's examination of the title discloses liens, a portion of the purchase price can be withheld from the seller. The withheld portion is used to pay the liens to clear the title.

If the seller cannot clear the title, or if for any reason the sale cannot be consummated, the escrow instructions usually provide that the parties be returned to their former statuses, as if no sale occurred. The escrow agent reconveys title to the seller and returns the purchase money to the buyer.

Internal Revenue Service Reporting Requirements

Certain real estate closings must be reported to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) on Form 1099-S. The affected properties include sales or exchanges of land (improved or unimproved), including air space;

► an inherently permanent structure, including any residential, commercial, or industrial building;

► a condominium unit and its appurtenant fixtures and common elements (including land); or

► stock in a cooperative housing corporation.

Information to be reported includes the sales price, the amount of property tax reimbursement credited to the seller, and the seller's Social Security number. If the closing agent does not notify the IRS, the responsibility for filing the form falls on the mortgage lender, although the brokers or the parties to the transaction ultimately could be held liable.

Broker's Role at Closing

Depending on local practice, the broker's role at closing can vary from simply collecting the commission to conducting the proceedings. Real estate brokers are not authorized to give legal advice or otherwise engage in the practice of law. This means that in some states, a broker's job is essentially finished as soon as the real estate sales contract is signed. After the contract is signed, the attorneys take over. Even so, a broker's service generally continues all the way through closing. The broker makes sure all the details are taken care of so that the closing can proceed smoothly. This means making arrangements for title evidence, surveys, appraisals, inspections or repairs for structural conditions, water supplies, sewerage facilities, or toxic substances.

Though real estate licensees do not always conduct closing proceedings, they usually attend. Often, the parties look to their agents for guidance, assistance, and information during what can be a stressful experience. Licensees need to be thoroughly familiar with the process and procedures involved in preparing a closing statement, which includes the expenses and prorations of costs to close the transaction. It is also in the brokers' best interests that the transactions they worked so hard to bring about move successfully and smoothly to a conclusion. Of course, a broker's (and a salesperson's) commission is generally paid out of the proceeds at closing.

IN PRACTICE Licensees should avoid recommending sources for any inspection or testing services. If a buyer suffers any injury as a result of a provider's negligence, the licensee may also be liable. The better practice is to give clients the names of several professionals who offer high-quality services.

Lender's Interest in Closing

Whether a buyer obtains new financing or assumes the seller's existing loan, the lender wants to protect its security interest in the property. The lender has an interest in making sure the buyer gets good, marketable title and that tax and insurance payments are maintained. Lenders want their mortgage liens to have priority over other liens. They also want to ensure that insurance is kept up to date in case property is damaged or destroyed. For this reason, a lender generally requires a title insurance policy and a fire and hazard insurance policy (along with a receipt for the premium). In addition, a lender may require other information: a survey, a termite or another inspection report, or a certificate of occupancy (for a newly constructed building). A lender also may request that a reserve account be established for tax and insurance payments. Lenders sometimes even require representation by their own attorneys at closings.

RESPA REQUIREMENTS

The federal Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA) was enacted to protect consumers from abusive lending practices. RESPA also aids consumers during the mortgage loan settlement process. It ensures that consumers are provided with important, accurate, and timely information about the actual costs of settling or closing a transaction. It also eliminates kickbacks and other referral fees that tend to inflate the costs of settlements unnecessarily. RESPA prohibits lenders from requiring excessive escrow account deposits.

RESPA requirements apply when a purchase is financed by a federally related mortgage loan. Federally related loans means loans made by banks, savings and loan associations, or other lenders whose deposits are insured by federal agencies. It also includes loans insured by the FHA and guaranteed by the VA; loans administered by HUD; and loans intended to be sold by the lenders to Fannie Mae, Ginnie Mae, or Freddie Mac. RESPA is administered by HUD.

RESPA regulations apply to first-lien residential mortgage loans made to finance the purchases of one-family to four-family homes, cooperatives, and condominiums, for either investment or occupancy. RESPA also governs second or subordinate liens for home equity loans. A transaction financed solely by a purchase-money mortgage taken back by the seller, an installment contract (contract for deed), and a buyer's assumption of a seller's existing loan are not covered by RESPA. However, if the terms of the assumed loan are modified, or if the lender charges more than $50 for the assumption, the transaction is subject to RESPA regulations.

IN PRACTICE While RESPA's requirements are aimed primarily at lenders, some provisions of the Act affect real estate brokers and agents as well. Real estate licensees fall under RESPA when they refer buyers to particular lenders, title companies, attorneys, or other providers of settlement services. Licensees who offer computerized loan origination (CLO) services also are subject to regulation. Remember: Buyers have the right to select their own providers of settlement services.

Controlled Business Arrangements

A service that is increasing in popularity is one-stop shopping for consumers of real estate services. A real estate firm, title insurance company, mortgage broker, home inspection company, or even a moving company may agree to offer a package of services to consumers. RESPA permits such a controlled business arrangement (CBA) as long as a consumer is clearly informed of the relationship among the service providers and that other providers are available. Fees may not be exchanged among the affiliated companies simply for referring business to one another. This may be a particularly important issue for licensees who offer cornputerized loan origination (CLO) services to their clients and customers (discussed in Chapter 15). While a borrower's ability to comparison shop for a loan may be enhanced by a CLO system, his or her range of choices must not be limited. Consumers must be informed of the availability of other lenders.

Disclosure Requirements

Lenders and settlement agents have the following disclosure obligations at the time of loan application and loan closing:

► Special information booklet. Lenders must provide a copy of a special informational HUD booklet to every person from whom they receive or for whom they prepare a loan application (except for refinancing). The HUD booklet must be given at the time the application is received or within three days afterward. The booklet provides the borrower with general information about settlement (closing) costs. It also explains the various provisions of RESPA, including a line-by-line description of the Uniform Settlement Statement.

► Good-faith estimate of settlement costs. No later than three business days after receiving a loan application, the lender must provide to the borrower a good-faith estimate of the settlement costs the borrower is likely to incur. This estimate may be either a specific figure or a range of costs based on comparable past transactions in the area. In addition, if the lender requires use of a particular attorney or title company to conduct the closing, the lender must state whether it has any business relationship with that firm and must estimate the charges for this service.

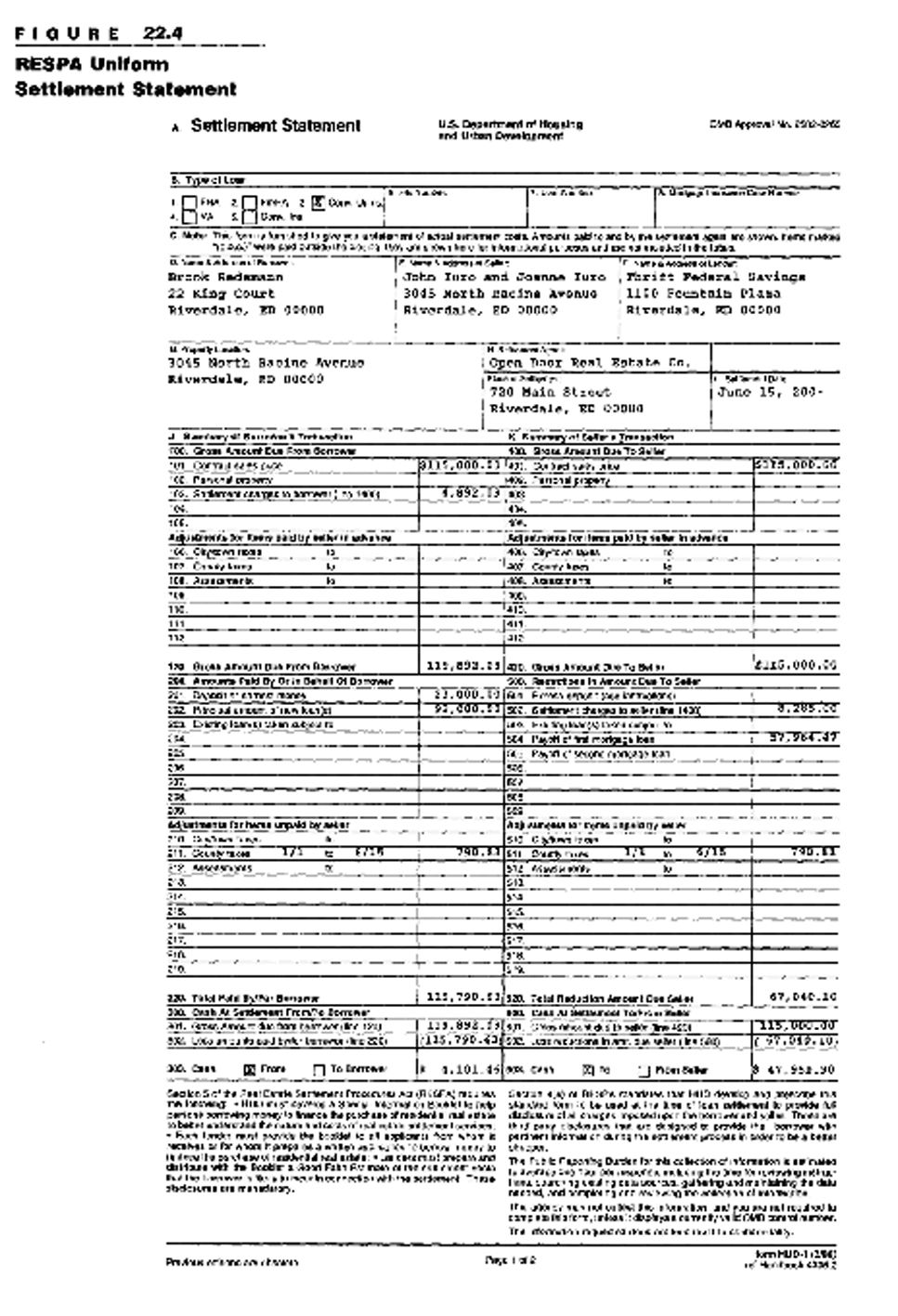

► Uniform Settlement Statement (HUD-1 Form). RESPA requires that a special HUD form be completed to itemize all charges to be paid by a borrower and seller in connection with settlement. The Uniform Settlement Statement includes all charges that will be collected at closing, whether required by the lender or another party. Items paid by the borrower and seller outside closing and not required by the lender are not included on the HUD-1 form. Charges required by the lender that are paid for before closing are indicated as "paid outside of closing" (POC). RESPA prohibits lenders from requiring borrowers to deposit amounts in escrow accounts for taxes and insurance that exceed certain limits, thus preventing the lenders from taking advantage of the borrowers. Sellers are also prohibited from requiring, as a condition of a sale, that the buyer purchase title insurance from a particular company. A copy of the HUD-1 form is illustrated later in this Chapter. (See Figure 22.4.)

The settlement statement must be made available for inspection by the borrower at or before settlement. Borrowers have the right to inspect a completed HUD-1 form, to the extent that the figures are available, one business day before the closing. (Sellers are not entitled to this privilege.)

Lenders must retain these statements for two years after the dates of closing. In addition, state laws generally require that licensees retain all records of a transaction for a specific period. The Uniform Settlement Statement may be altered to allow for local custom, and certain lines may be deleted if they do not apply in an area.

Kickbacks and referral fees.

RESPA prohibits the payment of kickbacks, or unearned fees, in any real estate settlement service. It prohibits referral fees when

no services are actually rendered. The payment or receipt of a fee, a kickback, or

anything of value for referrals for settlement services includes activities such as mortgage loans, title searches, title insurance, attorney services, surveys, credit reports, and appraisals.

PREPARATION OF CLOSING STATEMENTS

A typical real estate transaction involves, in addition to the purchase price, expenses for both parties. These include items prepaid by the seller for which he or she must be reimbursed (such as taxes) and items of expense the seller has incurred, but for which the buyer will be billed (such as mortgage interest paid in arrears when a loan is assumed).

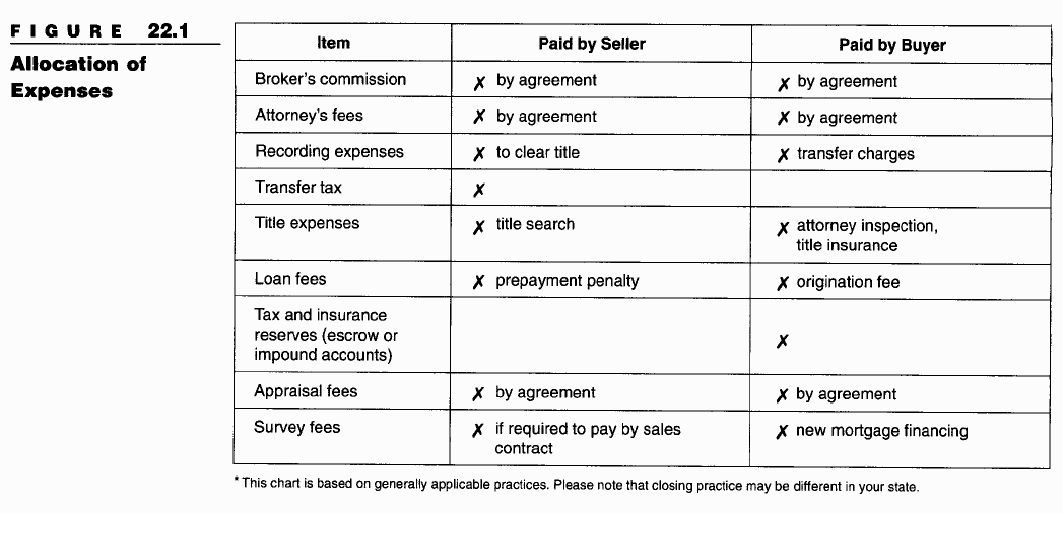

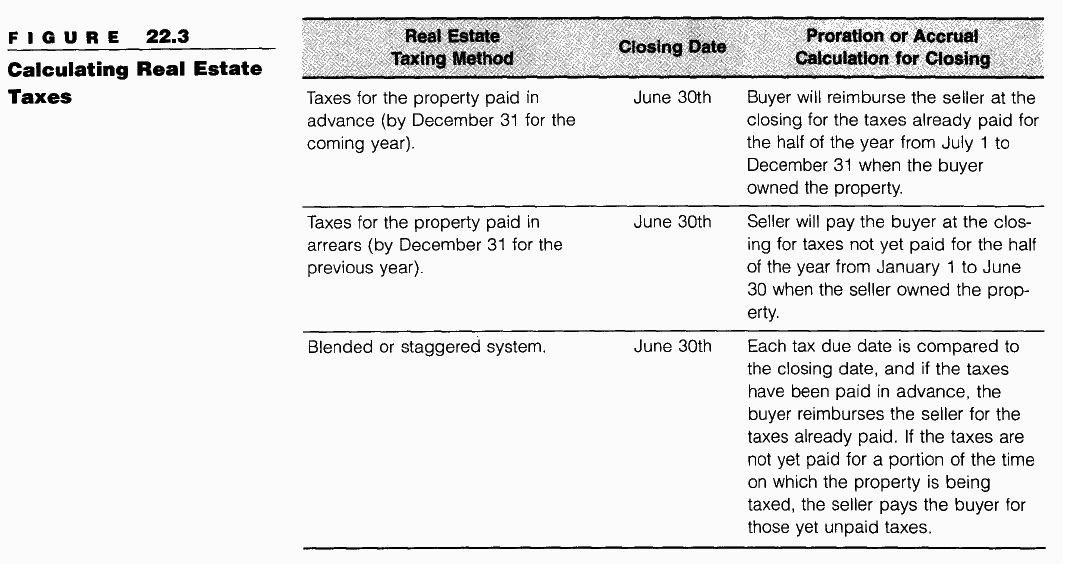

The financial responsibility for these items must be prorated (or divided) between the buyer and the seller. All expenses and prorated items are accounted for on the settlement statement. This is how the exact amount of cash required from the buyer and the net proceeds to the seller are determined. (See Figure 22.1.)

How the Closing Statement Works

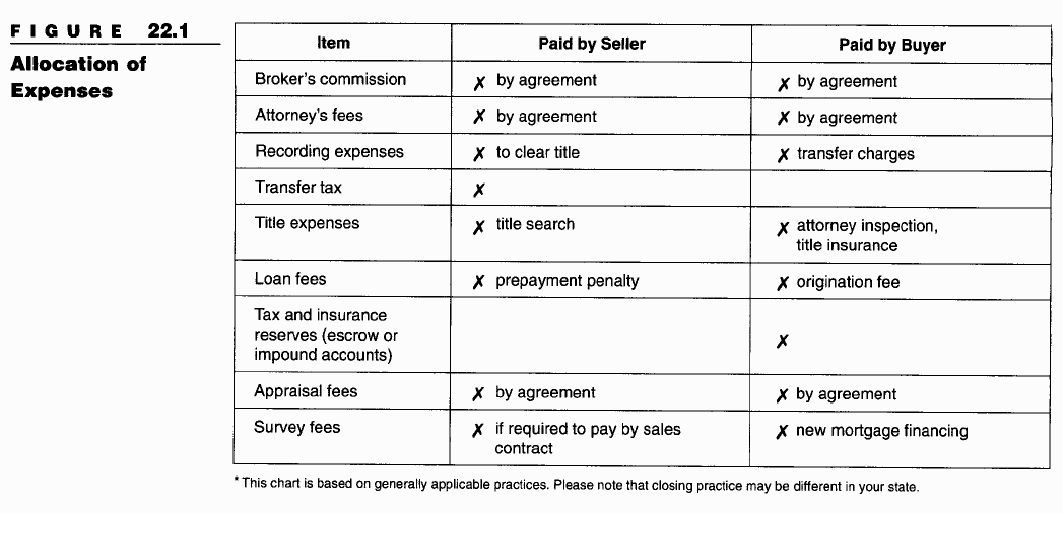

The completion of a closing statement involves an accounting of the parties' debits and credits. A debit is a charge, that is, an amount that a party owes and must pay at closing. A credit is an amount entered in a person's favor—an amount that has already been paid, an amount being reimbursed, or an amount the buyer promises to pay in the form of a loan.

To determine the amount a buyer needs at closing, the buyer's debits are totaled. Any expenses and prorated amounts for items prepaid by the seller are added to the purchase price. Then the buyer's credits are totaled. These include the earnest money (already paid), the balance of the loan the buyer obtains or assumes, and the seller's share of any prorated items the buyer will pay in the future. (See Figure 22.2.) Finally, the total of the buyer's credits is subtracted from the total debits to arrive at the actual amount of cash the buyer must bring to closing. Usually, the buyer brings a cashier's or certified check.

A similar procedure is followed to determine how much money the seller will actually receive. The seller's debits and credits are each totaled. The credits include the purchase price plus the buyer's share of any prorated items that the seller has prepaid. The seller's debits include expenses, the seller's share of prorated items to be paid later by the buyer, and the balance of any mortgage loan or other lien that the seller pays off. Finally, the total of the seller's debits is subtracted from the total credits to arrive at the amount the seller will receive.

Broker's commission.

The responsibility for paying the broker's commission will have been determined by previous agreement. If the broker is the agent for the seller, the seller is normally responsible for paying the commission. If an agency agreement exists between a broker and the buyer, or if two agents are involved, one for the seller and one for the buyer, the commission may be apportioned as an expense between both parties or according to some other arrangement.

Attorney's fees.

If either of the parties' attorneys will be paid from the closing proceeds, that party will be charged with the expense in the closing statement. This expense may include fees for the preparation or review of documents or for representing the parties at settlement.

Recording expenses.

The seller usually pays for recording charges (filing fees) necessary to clear all defects and furnish the purchaser with a marketable title. Items customarily charged to the seller include the recording of release deeds or satisfaction of mortgages, quitclaim deeds, affidavits, and satisfaction of mechanics' liens. The purchaser pays for recording charges that arise from the actual transfer of title. Usually, such items include recording the deed that conveys title to the purchaser and a mortgage or deed of trust executed by the purchaser.

Transfer tax.

Most states require some form of transfer tax, conveyance fee, or tax stamps on real estate conveyances. This expense is most often borne by the seller, although customs vary. In addition, many cities and local municipalities charge transfer taxes. Responsibility for these charges varies according to local practice.

Title expenses.

Responsibility for title expenses varies according to local custom. In most areas, the seller is required to furnish evidence of good title and pay for the title search. If the buyer's attorney inspects the evidence or if the buyer purchases title insurance policies, the buyer is charged for the expense.

Loan fees.

When the buyer secures a new loan to finance the purchase, the lender ordinarily charges a loan origination fee of 1 percent to 2 percent of the loan. The fee is usually paid by the purchaser at the time the transaction closes. The lender may also charge discount points if the buyer has secured a loan with a below-market interest rate. If the buyer assumes the seller's existing financing, the buyer may pay an assumption fee. Also, under the terms of some mortgage loans, the seller may be required to pay a prepayment charge or penalty for paying off the mortgage loan before its due date.

Tax reserves and insurance reserves (escrow or impound accounts).

Most mortgage lenders require that borrowers provide reserve funds or escrow accounts to pay future real estate taxes and insurance premiums. A borrower starts the account at closing by depositing funds to cover at least the amount of unpaid real estate taxes from the date of lien to the end of the current month. (The buyer receives a credit from the seller at closing for any unpaid taxes.) Afterward, an amount equal to one month's portion of the estimated taxes is included in the borrower's monthly mortgage payment.

The borrower is responsible for maintaining adequate fire or hazard insurance as a condition of the mortgage loan. Generally, the first year's premium is paid in full at closing. An amount equal to one month's premium is paid after that. The borrower's monthly loan payment includes the principal and interest on the loan, plus one-twelfth of the estimated taxes and insurance (PITI). The taxes and insurance are held by the lender in the escrow or impound account until the bills are due.

IN PRACTICE RESPA permits lenders to maintain a "cushion" equal to one-sixth of the total amount of taxes and insurance paid out of the account, that is, approximately two months of escrow payments. However, if state law or mortgage documents allow for a smaller cushion, that lesser amount prevails.

Appraisal fees.

Either the seller or the purchaser pays the appraisal fees, depending on who orders the appraisal. When the buyer obtains a mortgage, it is customary for the lender to require an appraisal. In this case, the buyer usually bears the cost, although this is always a negotiable item. If the fee is paid at the time of the loan application, it is reflected on the closing statement as having already been paid.

Survey fees.

The purchaser who obtains new mortgage financing customarily pays the survey fees. The sales contract may require that the seller furnish a survey.

Additional fees.

An FHA borrower owes a lump sum for payment of the mortgage insurance premium (MIP) if it is not financed as part of the loan. A VA mortgagor pays a funding fee directly to the VA at closing. If a conventional loan carries private mortgage insurance (PMI), the buyer prepays one year's insurance premium at closing.

Accounting for Expenses

Expenses paid out of the closing proceeds are debited only to the party making the payment. Occasionally, an expense item, such as an escrow fee, a settlement fee, or a transfer tax, may be shared by the buyer and the seller. In this case, each party is debited for the share of the expense.

PRORATIONS

Most closings involve the division of financial responsibility between the buyer and seller for such items as loan interest, taxes, rents, fuel, and utility bills. These allowances are called prorations. Prorations are necessary to ensure that expenses are divided fairly between the seller and the buyer. For example, the seller may owe current taxes that have not been billed; the buyer would want this settled at the closing. Where taxes must be paid in advance, the seller is entitled to a rebate at the closing. If the buyer assumes the seller's existing mortgage or deed of trust, the seller usually owes the buyer an allowance for accrued interest through the date of closing.

Accrued items are expenses to be prorated (such as water bills and interest on an assumed mortgage) that are owed by the seller, but later will be paid by the buyer. The seller therefore pays for these items by giving the buyer credits for them at closing.

Prepaid items are expenses to be prorated, such as fuel oil in a tank, that have been prepaid by the seller but not fully used up. They are therefore credits to the seller.

The Arithmetic of Prorating

Accurate prorating involves the following four considerations:

1) Nature of the item being prorated

2) Whether it is an accrued item that requires the determination of an earned amount

3) 'Whether it is a prepaid item that requires the determination of an unearned amount (that is, a refund to the seller)

4) What arithmetic processes must be used

The computation of a proration involves identifying a yearly charge for the item to be prorated, then dividing by 12 to determine a monthly charge for the item. Usually, it also is necessary to identify a daily charge for the item by dividing the monthly charge by the number of days in the month. These smaller portions are then multiplied by the number of months or days in the prorated time period to determine the accrued or unearned amount that will be figured in the settlement.

Using this general principle, there are two methods of calculating prorations:

1) The yearly charge is divided by a 360-day year (commonly called a banking year), or 12 months of 30 days each.

2) The yearly charge is divided by 365 (366 in a leap year) to determine the daily charge. Then the actual number of days in the proration period is determined, and this number is multiplied by the daily charge.

The final proration figure varies slightly, depending on which computation method is used. The final figure also varies according to the number of decimal places to which the division is carried. All of the computations in this Chapter are computed by carrying the division to three decimal places. The third decimal place is rounded off to cents only after the final proration figure is determined.

Accrued Items

When the real estate tax is levied for the calendar year and is payable during that year or in the following year, the accrued portion is for the period from January 1 to the date of closing (or to the day before the closing in states where the sale date is excluded). If the current tax bill has not yet been issued, the parties must agree on an estimated amount based on the previous year's bill and any known changes in assessment or tax levy for the current year.

Sample proration calculation.

Assume a sale is to be closed on September 17. Current real estate taxes of $1,200 are to be prorated. A 360-day year is used. The accrued period, then, is 8 months and 17 days. First determine the prorated cost of the real estate tax per month and day:

$1,200 ÷ 12 months = $100 per month

$100 ÷ 30 days = $3.333 per day

Next, multiply these figures by the accrued period, and add the totals to determine the prorated real estate tax:

$100 x 8 months = $800

$3.333 x 17 days = $56.661

$800.000 + 56.661 = $856.661

Thus, the accrued real estate tax for 8 months and 17 days is $856.66 (rounded off to two decimal places after the final computation). This amount represents the seller's accrued earned tax. It will be a credit to the buyer and a debit to the seller on the closing statement.

To compute this proration using the actual number of days in the accrued period, the following method is used: The accrued period from January 1 to September 17 runs 260 days (January's 31 days plus February's 28 days and so on, plus the 17 days of September).

$1,200 tax bill ÷ 365 days = $3.288 per day

$3.288 x 260 days = $854.880, or $854.88

While these examples show proration as of the date of settlement, the agreement of sale may require otherwise. For instance, a buyer's possession date may not coincide with the settlement date. In this case, the parties could prorate according to the date of possession.

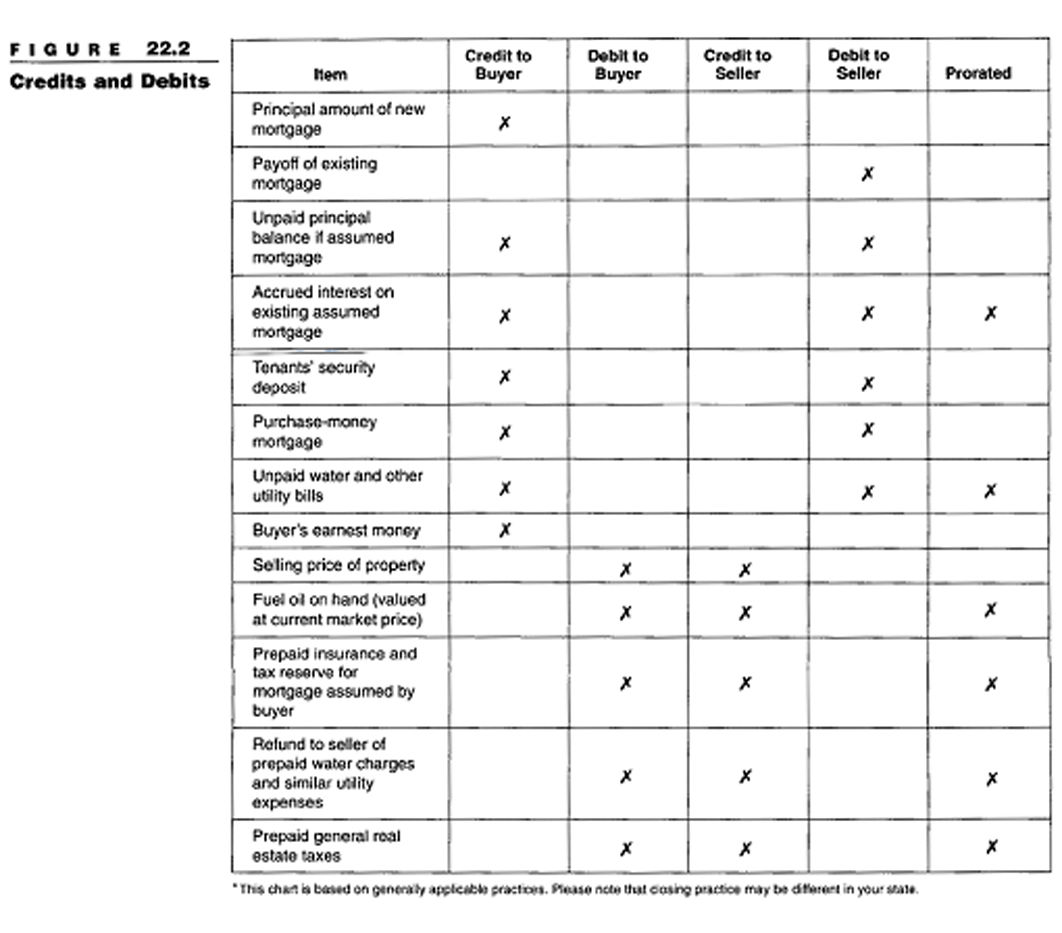

IN PRACTICE On state licensing examinations, tax prorations are usually based on a 30-day month (360-day year) unless specified otherwise. This may differ with local customs regarding tax prorations. Many title insurance companies provide proration charts that detail tax factors for each day in the year. To determine a tax proration using one of these charts, multiply the factor given for the closing date by the annual real estate tax. (See Figure 22.3.)

Prepaid Items

A tax proration could be a prepaid item. Because real estate taxes may be paid in the early part of the year, a tax proration calculated for a closing taking place later in the year must reflect the fact that the seller has already paid the tax. For example, in the preceding problem, suppose that all taxes had been paid. The buyer, then, would have to reimburse the seller; the proration would be credited to the seller and debited to the buyer.

In figuring the tax proration, it is necessary to ascertain the number of future days, months, and years for which taxes have been paid. The formula commonly used for this purpose is as follows:

Years Months Days

Taxes paid to (Dec. 31, end of tax year) 200_ 12 30

Date of closing (Sept. 17, 200_) 200_ - 9 -17

Period for which tax must be paid 3 13

With this formula, we can find the amount the buyer will reimburse the seller for the unearned portion of the real estate tax. The prepaid period, as determined using the formula for prepaid items, is 3 months and 13 days. Three months at $100 per month equals $300, and 13 days at $3.333 per day equals $43.33. Add this to determine that the proration is $343.33 credited to the seller and debited to the buyer.

Sample prepaid item calculation.

One example of a prepaid item is a water bill. Assume that the water is billed in advance by the city without using a meter. The six months' billing is $60 for the period ending October 31. The sale is to be closed on August 3. Because the water bill is paid to October 31, the pre-paid time must be computed. Using a 30-day basis, the time period is the 27 days left in August plus two full months: $60 ( 6 = $10 per month. For one day, divide $10 by 30, which equals $0.333 per day. The prepaid period is 2 months and 27 days, so:

27 x $0.333 per day = $8.991

2 months x $10 = $20.000

$28.991 or $28.99

This is a prepaid item; it is credited to the seller and debited to the buyer on the closing statement.

To figure this based on the actual days in the month of closing, the following process would be used:

$10 per month ÷ 31 days in August = $0.323 per day

August 4 through August 31 = 28 days

28 days x $0.323 = $9.044

2 months x $10 = $20.000

$9.044 + $20 = $29.044, or $29.04

General Rules for Prorating

The rules or customs governing the computation of prorations for the closing of a real estate sale vary widely from state to state. The following are some general guidelines for preparing the closing statement:

► In most states, the seller owns the property on the day of closing, and prorations or apportionments are usually made to and including the day of closing. In a few states, however, it is provided specifically that the buyer owns the property on the closing date. In that case, adjustments are made as of the day preceding the day on which title is closed.

► Mortgage interest, general real estate taxes, water taxes, insurance premiums, and similar expenses are usually computed by using 360 days in a year and 30 days in a month. However, the rules in some areas provide for computing prorations on the basis of the actual number of days in the calendar month of closing. The agreement of sale should specify which method will be used.

► Accrued or prepaid general real estate taxes are usually prorated at the closing. When the amount of the current real estate tax cannot be determined definitely, the proration is usually based on the last obtainable tax bill.

► Special assessments for municipal improvements such as sewers, water mains, or streets are usually paid in annual installments over several years, with annual interest charged on the outstanding balance of future installments. The seller normally pays the current installment, and the buyer assumes all future installments. The special assessment installment generally is not prorated at the closing. A buyer may insist that the seller allow the buyer a credit for the seller's share of the interest to the closing date. The agreement of sale may address the manner in which special assessments will be handled at settlement.

► Rents are usually adjusted on the basis of the actual number of days in the month of closing. It is customary for the seller to receive the rents for the day of closing and to pay all expenses for that day. If any rents for the current month are uncollected when the sale is closed, the buyer often agrees by a separate letter to collect the rents if possible and remit the pro rata share to the seller.

► Security deposits made by tenants to cover the last month's rent of the lease or to cover the cost of repairing damage caused by the tenant are generally transferred by the seller to the buyer.

Real estate taxes.

Proration of real estate taxes varies widely depending on how the taxes are paid in the area where the real estate is located. In some states, real estate taxes are paid in advance; that is, if the tax year runs from January 1 to December 31, taxes for the coming year are due on January 1. In this case, the seller, who has prepaid a year's taxes, should be reimbursed for the portion of the year remaining after the buyer takes ownership of the property. In other areas, taxes are paid in arrears, on December 31 for the year just ended. In this case, the buyer should be credited by the seller for the time the seller occupied the property. Sometimes, taxes are due during the tax year, partly in arrears and partly in advance; sometimes they are payable in installments. It gets even more complicated: City, state, school, and other property taxes may start their tax years in different months. Whatever the case may be in a particular transaction, the licensee should understand how the taxes will be prorated.

Mortgage loan interest.

On almost every mortgage loan the interest is paid in arrears, so the buyer and seller must understand that the mortgage payment due on June 1, for example, includes interest due for the month of May. Thus, the buyer who assumes a mortgage on May 31 and makes the June payment pays for the time the seller occupied the property and should be credited with a month's interest. On the other hand, the buyer who places a new mortgage loan on May 31 may be pleasantly surprised to hear that he or she will not need to make a mortgage payment until a month later.

SAMPLE CLOSING STATEMENT

Settlement computations take many possible formats. The remaining portion of this Chapter illustrates a sample transaction using the RESPA Uniform Settlement Statement in Figure 22.4. Because customs differ in various parts of the country, the way certain expenses are charged in some locations may be different from the illustration.

Basic Information of Offer and Sale

John and Joanne Iuro list their home at 3045 North Racine Avenue in Riverdale, East Dakota, with the Open Door Real Estate Company. The listing price is $118,500, and possession can be given within two weeks after all parties have signed the contract. Under the terms of the listing agreement, the sellers agree to pay the broker a commission of 6 percent of the sales price.

On May 18, the Open Door Real Estate Company submits a contract offer to the Iuros from Brook Redemann, a bachelor residing at 22 King Court, Riverdale. Redemann offers $115,000, with earnest money and down payment of $23,000 and the remaining $92,000 of the purchase price to be obtained through a new conventional loan. No private mortgage insurance is necessary because the loan-to-value ratio does not exceed 80 percent. The Iuros sign the contract on May 29. Closing is set for June 15 at the office of the Open Door Real Estate Company, 720 Main Street, Riverdale.

The unpaid balance of the Iuros' mortgage as of June 1, 200– will be $57,700. Payments are $680 per month, with interest at 11 percent per annum on the unpaid balance.

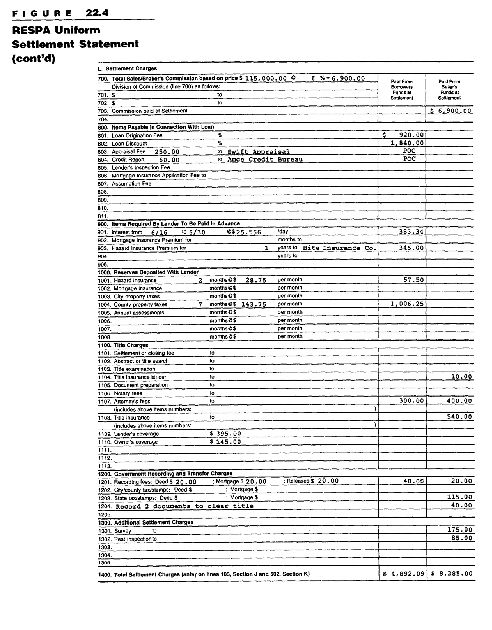

The sellers submit evidence of title in the form of a title insurance binder at a cost of $10. The title insurance policy, to be paid by the sellers at the time of closing, costs an additional $540, including $395 for lender's coverage and $145 for homeowner's coverage. Recording charges of $20 are paid for the recording of two instruments to clear defects in the sellers' title. State transfer tax stamps in the amount $115 ($.50 per $500 of the sales price or fraction thereof) are affixed to the deed. In addition, the sellers must pay an attorney's fee of $400 for preparing of the deed and for legal representation. This amount will be paid from the closing proceeds.

The buyer must pay an attorney's fee of $300 for examining the title evidence and for legal representation. He also must pay $20 to record the deed. These amounts also will be paid from the closing proceeds.

Real estate taxes in Riverdale are paid in arrears. Taxes for this year, estimated at last year's figure of $1,725, have not been paid. According to the contract, prorations will be made on the basis of 30 days in a month.

Computing the prorations and charges.

The following list illustrates the various steps in computing the prorations and other amounts to be included in the settlement to this point:

► Closing date: June 15

► Commission: 6% (.06) x $115,000 sales price = $6,900

► Seller's mortgage interest: 11% (.11) x $57,700 principal due after June 1

payment = $6,347 interest per year; $6,347 ÷ 360 days = $17.631 interest per day;

15 days of accrued interest to be paid by the seller x $17.631 = $264.465 interest owed by the seller;

$57,700 + $264.465 = $57,964.465, or $57,964.47 payoff of seller's mortgage

► Real estate taxes (estimated at $1,725): $1,725 ÷ 12 months = $143.75 per month;

$143.75 ÷ 30 days = $ 4.792 per day

► The earned period, from January 1 to and including June 15, equals five months and 15 days: $143.75

x 5 months = $718.75; $4.792 x 15 days = $71.88; $718.75 + $71.88 = $790.63 seller owes buyer

► Transfer tax ($.50 per $500 of consideration or fraction thereof): $115,000 ÷ $500 = $230;

$230 x $.50 = $115 transfer tax owed by seller

The sellers' loan payoff is $57,964.47. They must pay an additional $20 to record the mortgage release, as well as $85 for a pest inspection and $175 for a survey, as negotiated between the parties. The buyer's new loan is from Thrift Federal Savings, 1100 Fountain Plaza, Riverdale, in the amount of $92,000 at 10 percent interest. In connection with this loan, Redemann will be charged $250 to have the property appraised by Swift Appraisal. Acme Credit Bureau will charge $60 for a credit report. (Because appraisal and credit reports are performed before loan approval, they are paid at the time of loan application, whether or not the transaction eventually closes. These items are noted as POC—paid outside closing—on the settlement statement.) In addition, Redemann will pay for interest on his loan for the remainder of the month of closing: 15 days at $25.556 per day, or $383.34. His first full payment (including July's interest) will be due on August 1. He must deposit $1,006.25 into a tax reserve account. That's 7/12 of the anticipated county real estate tax of $1,725. A one-year hazard insurance premium at $3 per $1,000 of appraised value ($115,000 ÷ 1,000 x 3 = $345) is paid in advance to Hite Insurance Company. An insurance reserve to cover the premium for two months is deposited with the lender. Redemann will have to pay an additional $20 to record the mortgage. He will also pay a loan origination fee of $920 and two discount points of $1,840.

The Uniform Settlement Statement

The Uniform Settlement Statement is divided into 12 sections. Sections J, K, and L contain particularly important information. The borrower's and seller's summaries (J and K) are very similar. In Section J, the buyer-borrower's debits are listed on lines 100 through 112. They are totaled on line 120 (gross amount due from borrower). The total of the settlement costs itemized in Section L of the statement is entered on line 103 as one of the buyer's charges. The buyer's credits are listed on lines 201 through 219 and totaled on line 220 (total paid by or for borrower). Then the buyer's credits are subtracted from the charges to arrive at the cash due from the borrower to close (line 303).

In Section K, the seller's credits are entered on lines 400 through 412 and totaled on line 420 (gross amount due to seller). The seller's debits are entered

on lines 501 through 519 and totaled on line 520 (total reduction amount due seller). The total of the seller's settlement charges is on line 502. Then the debits are subtracted from the credits to arrive at the cash due to the seller to close (line 603).

Section L summarizes all the settlement charges for the transaction; the buyer's expenses are listed in one column and the seller's expenses in the other. If an attorney's fee is listed as a lump sum in line 1107, the settlement should list by line number the services that were included in that total fee.

SUMMARY

Closing a real estate sale involves both title procedures and financial matters. The real estate salesperson or broker is often present at the closing to see that the sale is actually concluded and to account for the earnest money deposit.

The federal Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA) requires disclosure of all settlement costs when a residential real estate purchase is financed by a federally related mortgage loan. RESPA requires that lenders use a Uniform Settlement Statement to detail the financial particulars of a transaction.

The actual amount to be paid by a buyer at closing is computed on a closing, or settlement, statement. This lists the sales price, earnest money deposit and all adjustments and prorations due between buyer and seller. The purpose of this statement is to determine the net amount due the seller at closing. The buyer reimburses the seller for prepaid items such as unused taxes or fuel oil. The seller credits the buyer for bills the seller owes, but the buyer will have to pay accrued items such as unpaid water bills.

This short video will explain how debits and credits work on the "Closing Statement". From the text you may recall the completion of a closing statement involves an accounting of the parties' debits and credits. A debit is a charge, that is, an amount that a party owes and must pay at closing. A credit is an amount entered in a person's favor - or an amount that has already been paid, an amount being reimbursed, or an amount the buyer promises to pay in the form of a loan.