CHAPTER NINE

LEGAL DESCRIPTIONS

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

When you've finished reading this Chapter, you should be able to:

► identify the three methods used to describe real estate.

► describe how a survey is prepared.

► explain how to read a rectangular survey description.

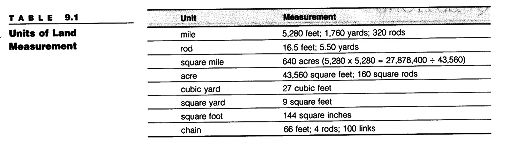

► distinguish the various units of land measurement.

► define the following key terms: air lots, legal description, principal meridians, base lines, lot-and-block (recorded plat) system, ranges,

benchmarks, rectangular (government survey system), correction lines , metes-and-bounds description, datum, sections, fractional sections, monuments, townships, plat map, township lines, government check, point of beginning (POB), township tiers, and government lots.

REAL ESTATE PRACTICE & PRINCIPLES KEY WORD MATCH QUIZ

--- CLICK HERE ---

I would encourage you to take this “Match quiz” now as a pre-chapter challenge to see how many of these key words or phrases you are familiar with. At the end of each chapter I recommend that you take the quiz again to reinforce these important keywords. Each page contains four words or phrases and you need to drag and drop the correct definition into the puzzle key. Each page is considered as a question, but there is no scoring and you can return to each chapter quiz as many times as needed to reinforce your memory.

► WHY LEARN ABOUT... LEGAL DESCRIPTIONS ?

Because your customers are paying a lot of money for their real estate, they expect to become the owners of every bit of land they're entitled to. Certainly the lawyers will review the plats and make sure the legal descriptions are accurate, but the licensee should be able to at least know what, in general, the lawyers are talking about. Knowing how land is described, and understanding the reasoning behind it, will help you gain a firmer comprehension of the product your profession deals in.

► DESCRIBING LAND

People often refer to real estate by its street address, such as "1234 Main Street." While that is usually enough for the average person to find a particular building, it is not precise enough to be used on documents affecting the ownership of land. Further, addresses can change as streets are renamed or rural roads become absorbed into growing communities. Sales contracts, deeds, mortgages, and trust deeds, for instance, require a much more specific (or legally sufficient) description of property to be binding.

Courts have stated that a description is legally sufficient if it allows a competent surveyor to locate the parcel. In this context, however, "locate" means the surveyor must be able to define the exact boundaries of the property. The street address "1234 Main Street" would not tell a surveyor how large the property is or where it begins and ends. Several alternative systems of identification have been developed that express a legal description of real estate: one that is sufficiently specific that an independent surveyor could locate the exact dimensions of the property being described.

► METHODS OF DESCRIBING REAL ESTATE

Three basic methods can be used to describe real estate:

1. Metes and bounds

2. Rectangular (or government) survey

3. Lot and block (recorded plat)

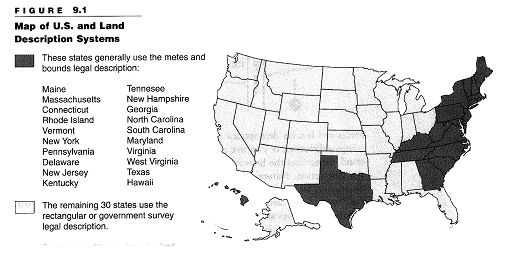

Although each method can be used independently, the methods may be combined in some situations. Some states use only one method; others use all three. (See Figure 9.1.)

Metes-and-Bounds Method

The metes-and-bounds description is the oldest type of legal description. Metes

Method means distance, and bounds means compass directions or angles. The method relies on a property's physical features to determine the boundaries and measurements of the parcel. A metes-and-bounds description starts at a designated place on the parcel, called the point of beginning (POB). From there, the surveyor proceeds around the property's boundaries. The boundaries are recorded by referring to linear measurements, natural and artificial landmarks (called monuments), and directions. A metes-and-bounds description always ends back at the POB so that the tract being described is completely enclosed.

Monuments are fixed objects used to identify the POB, the ends of boundary segments, or the location of intersecting boundaries. A monument may be a natural object, such as a stone, large tree, lake, or stream. It also may be a human-made object, such as a street, highway, fence, canal, or markers (iron pins or concrete posts) placed by surveyors. Measurements often include the words more or less because the location of the monuments is more important than the distance stated in the wording. The actual distance between monuments takes precedence over any linear measurements in the description.

An example of a metes-and-bounds description of a parcel of land (pictured in Figure 9.2) follows:

A tract of land located in Red Skull, Boone County, Virginia, described as follows: Beginning at the intersection of the east line of Jones Road and the south line of Skull Drive; then east along the south line of Skull Drive 200 feet; then south 15° east 216.5 feet, more or less, to the center thread of Red Skull Creek then northwesterly along the center line of said creek to its intersection with the east line of Jones Road; then north 105 feet, more or less, along the east line of Jones Road to the point of beginning.

When used to describe property within a town or city, a metes-and-bounds description may begin as follows:

Beginning at a point on the southerly side of Kent Street, 100 feet easterly from the corner formed by the intersection of the southerly side of Kent Street and the easterly side of Broadway; then...

In this description, the POB is given by reference to the corner intersection. Again, the description must close by returning to the POB.

Metes-and-bounds descriptions can be complex. When they include detailed compass directions or concave and convex lines, they can be difficult to under-stand. Sometimes the lines are curved on an arc or radius that becomes part of the description. Natural deterioration or destruction of the monuments in a description can make boundaries difficult to identify. For instance, "Raney's Oak" may have died long ago, and "Hunter's Rock" may no longer exist. Computer programs are available that convert the data of the compass directions and dimensions to a drawing that verifies that the description closes to the POB. Professional surveyors should be consulted for definitive interpretations of any legal description.

Rectangular (Government) Survey System

The rectangular survey system, sometimes called the government survey system, was established by Congress in 1785 to standardize the description of land acquired by the newly formed federal government. By dividing the land into rectangles, the survey provided land descriptions by describing the rectangle(s) in which the land was located. The system is based on two sets of intersecting lines: principal meridians and base lines. The principal meridians run north and south, and the base lines run east and west. Both are located by reference to degrees of longitude and latitude. Each principal meridian has a name or number and is crossed by a base line. Each principal meridian and its corresponding base line are used to survey a definite area of land, indicated on the map by boundary lines. There are 35 principal meridians in the United States.

Each principal meridian describes only specific areas of land by boundaries. No parcel of land is described by reference to more than one principal meridian. The meridian used may not necessarily be the nearest one.

Further divisions are used in the same way as monuments in the metes-and-bounds method. They are

► townships,

► ranges,

► sections, and

► quarter-section lines.

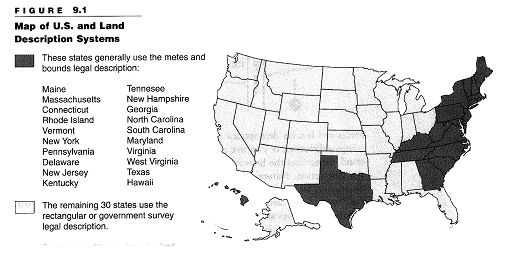

Township tiers. Lines running east and west, parallel to the base line and six miles apart, are referred to as township lines. They form strips of land called township tiers. (See Figure 9.3.) These township tiers are designated by consecutive numbers north or south of the base line. For instance, the strip of land between 6 and 12 miles north of a base line is Township 2 North.

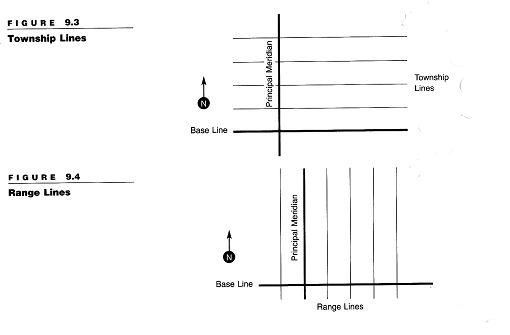

Ranges. The land on either side of a principal meridian is divided into six--mile-wide strips by lines that run north and south, parallel to the meridian. These north-south strips of land are called ranges. (See Figure 9.4.) They are designated by consecutive numbers east or west of the principal meridian. For example, Range 3 East would be a strip of land between 12 and 18 miles east of its principal meridian.

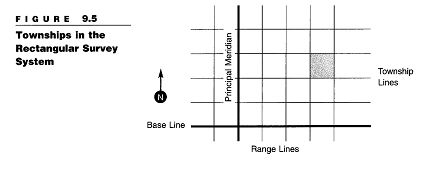

Township squares. When the horizontal township lines and the vertical range lines intersect, they form squares. These township squares are the basic units of the rectangular survey system. (See Figure 9.5.) Townships are 6 miles square and contain 36 square miles (23,040 acres).

Note that although a township square is part of a township tier, the two terms do not refer to the same thing. In this discussion, the word township used by itself refers only to the township square.

Each township is given a legal description. The township's description includes the following:

► Designation of the township tier in which the township is located

► Designation of the range strip

► Name or number of the principal meridian for that area

FOR EXAMPLE In Figure 9.5, (below) the shaded township is described as Township 3 North, Range 4 East of the Principal Meridian. This township is the third strip, or tier, north of the base line, and it designates the township number and direction. The township is also located in the fourth range strip (those running north and south) east of the principal meridian. Finally, reference is made to the principal meridian because the land being described is within the boundary of land surveyed from that meridian. This description is abbreviated as T3N, R4E 4th Principal Meridian.

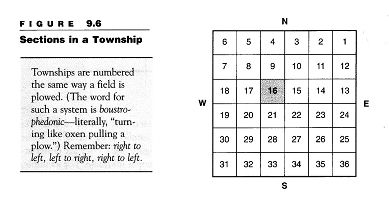

Sections. Township squares are subdivided into sections and subsections called "halves" and "quarters" that can be further divided. Each township contains 36 sections. Each section is one square mile, or 640 acres. Sections are numbered 1 through 36, as s own in Figure 9.6. Section 1 is always in the northeast, or upper right-hand, corner. The numbering proceeds right to left to the upper left-hand corner. From there, the numbers drop down to the next tier and continue from left to right, then back from right to left. By law, each section number 16 is set aside for school purposes. The sale or rental proceeds and were originally available for township school use. The schoolhouse was usually located in this section so it would be centrally located for all of the students in the town-ship. As a result, Section 16 is always referred to as a school section.

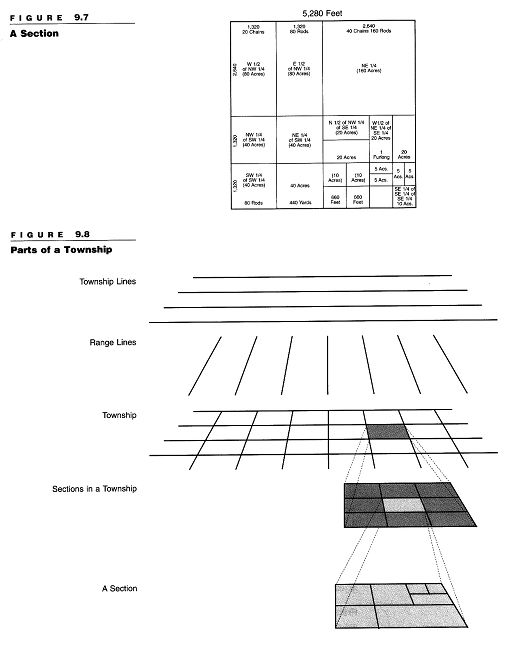

Sections are divided into halves (320 acres) and quarters (160 acres). (See Figure 9.7.) In turn, each of those parts is further divided into halves and quarters. The southeast quarter of a section, which is a 160-acre tract, is abbreviated SE ¼. The SE ¼ of SE ¼ of SE ¼ of Section 1 would be a ten-acre square in the lower right-hand corner of Section 1.

The rectangular survey system sometimes uses a shorthand method in its descriptions. For instance, a comma may be used in place of the word of: SE ¼, SE ¼ , SE ¼ , Section 1. It is possible to combine portions of a section, such as NE ¼ of SW¼ and N½ of NW¼ of SE ¼ of Section 1, which could also be written NE ¼, SW¼; N½, NW¼, SE¼ of Section 1. A semicolon means and. Because of the word and in this description, the area is 60 acres.

Starting with township and range lines, Figure 9.8 illustrates how sections are created and subdivided.

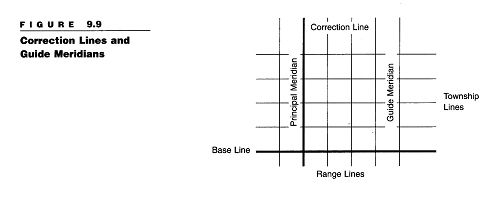

Correction lines. Range lines are parallel only in theory. Due to the curvature of the earth, range lines gradually approach each other. If they are extended northward, they eventually meet at the North Pole. The fact that the earth is not flat, combined with the crude instruments used in the early days, means that few townships are exactly six-mile squares or contain exactly 36 square miles. The system compensates for this "round earth problem" with correction lines. (See Figure 9.9.) Every fourth township line, both north and south of the base line, is designated a correction line. On each correction line, the range lines are measured to the full distance of six miles apart. Guide meridians run north and south at 24-mile intervals from the principal meridian. A government check is the area bounded by two guide meridians and two correction lines—an area approximately 24 miles square.

Because most townships do not contain exactly 36 square miles, surveyors follow well-established rules of adjustment. These rules provide that any irregularity in a township must be adjusted in those sections adjacent to its north and west boundaries (Sections 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 18, 19, 30, and 31). These are called fractional sections (discussed in the following paragraph). All other sections are exactly one square mile and are known as standard sections. These provisions for making corrections explain some of the variations in township and section acreage under the rectangular survey system of legal description.

Fractional sections and government lots. Undersized sections are classified as fractional sections. Fractional sections may occur for a number o reasons. In some areas, for instance, the rectangular survey may have been made by separate crews, and gaps less than a section wide remained when the surveys met. Other errors may have resulted from the physical difficulties 'encountered in the actual survey. For example, part of a section may be sub-merged in water.

Areas smaller than full quarter-sections were numbered and designated as government lots by surveyors. These lots can be created by the curvature of the earth, by land bordering or surrounding large bodies of water, or by artificial state borders. An overage or a shortage was corrected whenever possible by placing the government lots in the north or west portions of the fractional sections. For example, a government lot might be described as

Government Lot 2 in the northwest quarter of fractional Section 18, Township 2 North, Range 4 East of the Salt Lake Meridian.

Reading a rectangular survey description. To determine the location and size of a property described in the rectangular or government survey style, start at the end and work backward to the beginning, reading from right to left. For example, consider the following description:

The S½ of the NW¼ of the SE¼ of Section 11, Township 8 North, Range 6 West of the Fourth Principal Meridian.

To locate this tract of land from the citation alone, first search for the fourth principal meridian on a map of the United States and note its base line. Then, on a regional map, find the township in which the property is located by counting six range strips west of the fourth principal meridian and eight townships north of its corresponding base line. After locating Section 11, divide the section into quarters. Then divide the SE¼ into quarters, and then the NW¼ of that into halves. The S½ of that NW¼ contains the property in question.

In computing the size of this tract of land, first determine that the SE¼ of the section contains 160 acres (640 acres divided by 4). The NW¼ of that quarter-section contains 40 acres (160 acres divided by 4), and the S½ of that quarter-section—the property in question—contains 20 acres (40 acres divided by 2).

In general, if a rectangular survey description does not use the conjunction and or a semicolon (indicating various parcels are combined), the longer the description, the smaller the tract of land it describes.

Legal descriptions should always include the name of the county and state in which the land is located because meridians often relate to more than one state and occasionally relate to two base lines. For example, the description "the southwest quarter of Section 10, Township 4 North, Range 1 West of the Fourth Principal Meridian" could refer to land in either Illinois or Wisconsin.

Metes-and-bounds descriptions within the rectangular survey system. Land in states that use the rectangular survey system may also require a metes-and-bounds description. This usually occurs in one of three situations: (1) when describing an irregular tract; (2) when a tract is too small to be described by

quarter-sections; or (3) when a tract does not follow the lot or block lines of a recorded subdivision or section, quarter-section lines, or other fractional section lines. The following is an example of a combined metes-and-bounds and rectangular survey system description. (See Figure 9.10.)

That part of the northwest quarter of Section 12, Township 10 North, Range 7 West of the Third Principal Meridian, bounded by a line described as follows: Commencing at the southeast corner of the northwest quarter of said Section 12 then north 500 feet; then west parallel with the south line of said section 1,000 feet; then south parallel with the east line of said section 500 feet to the south line of said northwest quarter; then east along said south line to the point of beginning.

Lot-and-Block System

The third method of legal description is the lot-and-block (or recorded plat) system. This system uses lot-and-block numbers referred to in a plat filed in the public records of the county where the land is located. The lot-and-block system is often used to describe property in subdivisions.

A lot-and-block survey is performed in two steps. First, a large parcel of land is described either by the metes-and-bounds method or by rectangular survey. Once this large parcel is surveyed, it is broken into smaller parcels. As a result, a lot-and-block legal description always refers to a prior metes-and-bounds or rectangular survey description. For each parcel described under the lot-and-block system, the lot refers to the numerical designation of any particular parcel. The block refers to the name of the subdivision under which the map is record-ed. The block reference is drawn from the early 1900s, when a city block was the most common type of subdivided property.

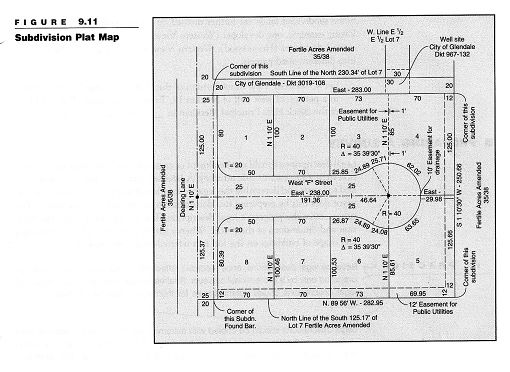

The lot-and-block system starts with the preparation of a subdivision plat by a licensed surveyor or an engineer. (See Figure 9.11.) On this plat, the land is divided into numbered or lettered lots and blocks, and streets or access roads for public use are indicated. Lot sizes and street details must be described completely and must comply with all local ordinances and requirements. When properly signed and approved, the subdivision plat is recorded in the county in which the land is located. The plat becomes part of the legal description. In describing a lot from a recorded subdivision plat, three identifiers are used:

1. Lot and block number

2. Name or number of the subdivision plat

3. Name of the county and state

The following is an example of a lot-and-block description:

Lot 71, Happy Valley Estates 2, located in a portion of the southeast quarter of Section 23, Township 7 North, Range 4 East of the Seward Principal Meridian in _____ County, ____ [state].

Anyone who wants to locate this parcel would start with the map of the Seward principal meridian to identify the township and range reference. Then he or she would consult the township map of Township 7 North, Range 4 East, and the section map of Section 23. From there, he or she would look at the quarter-section map of the southeast quarter. The quarter-section map would refer to the plat map for the subdivision known as the second unit (second parcel subdivided) under the name of Happy Valley Estates.

Some lot-and-block descriptions are not dependent on a government survey system and may refer to the plat recording in the land records of the county. An example might read: Being known and designated as Lot No. 15 on "Final Plat Section Two Waterford Subdivision" which plat is duly recorded among the land records of Baltimore County in Plat Book No. 27, Folio 59.

Some subdivided lands are further divided by a later resubdivision. In the following example, one developer (Western View) purchased a large parcel from a second developer (Homewood). Western View then resubdivided the property into different-sized parcels:

Lot 4, Western View Resubdivision of the Homewood Subdivision, located in a portion of west half of Section 19, Township 10 North, Range 13 East of the Black Hills Principal Meridian in _____ County,___ [state].

► PREPARING A SURVEY

Legal descriptions should not be altered or combined without adequate information from a surveyor or title attorney. A licensed surveyor is trained and authorized to locate and determine the legal description of any parcel of land. The surveyor does this by preparing two documents: a survey and a survey sketch. The survey states the property's legal description. The survey sketch shows the location and dimensions of the parcel. When a survey also shows the location, size, and shape of buildings on the lot, it is referred to as a spot survey.

IN PRACTICE Because legal descriptions, once recorded, affect title to real estate, they should be prepared only by a professional surveyor. Real estate licensees who attempt to draft legal descriptions create potential risks for themselves and their clients and customers.

Legal descriptions should be copied with extreme care. An incorrectly worded legal description in a sales contract may result in a conveyance of more or less land than the parties intended. Often, even punctuation is extremely critical. Title problems can arise for the buyer who seeks to convey the property at a future date. Even if the contract can be corrected before the sale is closed, the licensee risks losing a commission and may be held liable for damages suffered by an injured party because of an improperly worded legal description.

► MEASURING ELEVATIONS

Just as surface rights must be identified, surveyed, and described, so must rights to the property above the earth's surface. Recall from Chapter 2 that land includes the space above the ground. In the same way land may be measured and divided into parcels, the air itself may be divided. An owner may subdivide the air above his or her land into air lots. Air lots are composed of the airspace with-in specific boundaries located over a parcel of land.

The condominium laws passed in all states (see Chapter 8) require that a registered land surveyor prepare a plat map that shows the elevations of floor and ceiling surfaces and the vertical boundaries of each unit with reference to an official datum (discussed later in this Chapter). A unit's floor, for instance, might be 60 feet above the datum and its ceiling, 69 feet. Typically, a separate plat is prepared for each floor in the condominium building.

The following is an example of the legal description of a condominium apartment unit that includes a fractional share of the common elements of the building and land:

UNIT _______ as delineated on survey of the following described parcel of real estate (hereinafter referred to as Development Parcel): The north 99 feet of the west ½ of Block 4 (except that part, if any, taken and used for street), in Sutton's Division Number 5 in the east ½ of the southeast ¼ of Section 24, Township 3 South, Range 68 West of the Sixth Principal Meridian, in Denver County, Colorado, which survey is attached as Exhibit A to Declaration made by Colorado National Bank as Trustee under Trust No.1250, recorded in the Recorder's Office of Denver County, Colorado, as Document No. 475637; together with an undivided _______% interest in said Development Parcel (excepting from said Development Parcel all the property and space comprising all the units thereof as defined and set forth in said Declaration and Survey).

Subsurface rights can be legally described in the same manner as air rights. However, they are measured below the datum rather than above it. Subsurface rights are used not only for coal mining, petroleum drilling, and utility line location but also for multistory condominiums—both residential and commercial—that have several floors below ground level.

Datum

A datum is a point, line, or surface from which elevations are measured or indicated. For the purpose of the United States Geological Survey (USGS), datum is defined as the sea level at New York Harbor. A surveyor would use a datum in determining the height of a structure or establishing the grade of a street.

Benchmarks. Monuments are traditionally used to mark surface measurements between points. A monument could be a marker set in concrete, a piece of steel-reinforcing bar (rebar), a metal pipe driven into the soil, or simply a wooden stake stuck in the dirt. Because such items are subject to the whims of nature and vandals, their accuracy is sometimes suspect. As a result, surveyors rely most heavily on benchmarks to mark their work accurately and permanently.

Benchmarks are permanent reference points that have been established throughout the United States. They are usually embossed brass markers set into solid concrete or asphalt bases. While used to some degree for surface measurements, their principal reference use is for marking datums.

IN PRACTICE All large cities have established a local official datum used in place of the USGS datum. For instance, the official datum for Chicago is known as the Chicago City Datum. It is a horizontal plane that corresponds to the low-water .level of Lake Michigan in 1847 (the year in which the datum was established) and is considered to be at zero elevation. Although a surveyor's measurement of elevation based on the USGS datum will differ from one computed according to a local datum, it can be translated to an elevation based on the USGS.

Cities with local datums also have designated official local benchmarks, which are assigned permanent identifying numbers. Local benchmarks simplify surveyors' work because the basic benchmarks may be miles away.

LAND UNIT AND MEASUREMENTS

It is important to understand land units and measurements because they are integral parts of legal descriptions. Some commonly used measurements are listed in Table 9.1.