CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

REAL ESTATE APPRAISAL

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

When you've finished reading this Chapter, you should be able to:

► identify the different types and basic principles of value.

► describe the three basic valuation approaches used by appraisers.

► explain the steps in the appraisal process.

► distinguish the four methods of determining reproduction or replacement cost.

►define the following terms: budget comparison statement; cash flow report; corrective maintenance; management agreement; management plan; multiperil policies; operating budget; preventive maintenance; profit and loss statement; property manager risk; management routine maintenance; surety bonds; tenant improvements; and workers' compensation acts.

REAL ESTATE PRACTICE & PRINCIPLES KEY WORD MATCH QUIZ

--- CLICK HERE ---

I would encourage you to take this “Match quiz” now as a pre-chapter challenge to see how many of these key words or phrases you are familiar with. At the end of each chapter I recommend that you take the quiz again to reinforce these important keywords. Each page contains four words or phrases and you need to drag and drop the correct definition into the puzzle key. Each page is considered as a question, but there is no scoring and you can return to each chapter quiz as many times as needed to reinforce your memory.

WHY LEARN ABOUT... APPRAISAL?

Appraisal is a distinct area of specialization within the world of real estate professions. However, even real estate licensees who are not professional appraisers need to understand the fundamental principles of valuation to complete an accurate, effective, competitive market analysis (CMA) for their seller clients. Further, an understanding of the appraisal process will help you more clearly anticipate the likely out-come (and plan to avoid potential pitfalls) of a property's preclosing appraisal.

APPRAISING

An appraisal is an estimate or opinion of value based on supportable evidence and approved methods. An appraiser is an independent person trained to provide an unbiased estimate of value. Appraising is a professional service performed for a fee.

Regulation of Appraisal Activities

Title XI of the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989 (FIRREA) requires that any appraisal used in connection with a federally related transaction must be performed by a competent individual whose professional conduct is subject to supervision and regulation. Appraisers must be licensed or certified according to state law. Each state adopts its own appraiser regulations. These laws must conform to the federal requirements, which in turn follow the criteria for certification established by the Appraiser Qualifications Board of the Appraisal Foundation. The Appraisal Foundation is a national body composed of representatives of the major appraisal and related organizations. Appraisers are also expected to follow the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice established by the foundation's Appraisal Standards Board.

A federally related transaction is any real estate-related financial transaction in which a federal financial institution or regulatory agency engages. This includes transactions involving the sale, lease, purchase, investment, or exchange of real property. It also includes the financing, refinancing, or use of real property as security for a loan or an investment, including mortgage-backed securities. Appraisals of residential property valued at $250,000 or less and commercial property valued at $1 million or less in federally related transactions are exempt and need not be performed by licensed or certified appraisers.

Competitive Market Analysis

Not all estimates of value are made by professional appraisers. As discussed in Chapter 6, a salesperson often must help a seller arrive at a listing price or a buyer determine an offering price for property without the aid of a formal appraisal report. In such a case, the salesperson prepares a report compiled from research of the marketplace, primarily similar properties that have been sold, known as a competitive market analysis (CMA). The salesperson must be knowledgeable about the fundamentals of valuation to compile the market data. The competitive market analysis is not as comprehensive or technical as an appraisal and may be biased by a salesperson's anticipated agency relationship. A competitive market analysis should not be represented as an appraisal.

VALUE

To have value in the real estate market—that is, to have monetary worth based on desirability—a property must have the following characteristics:

► Demand—the need or desire for possession or ownership backed by the financial means to satisfy that need

► Utility—the property's usefulness for its intended purposes

► Scarcity—a finite supply

► Transferability—the relative ease with which ownership rights are transferred from one person to another

Market Value

Generally, the goal of an appraiser is to estimate market value. The market value of real estate is the most probable price that a property should bring in a fair sale. This definition makes three assumptions. First, it presumes a competitive and open market. Second, the buyer and seller are both assumed to be acting prudently and knowledgeably. Third, market value depends on the price not being affected by unusual circumstances.

The following are essential to determining market value:

► The most probable price is not the average or highest price.

► The buyer and seller must be unrelated and acting without undue pressure.

► Both buyer and seller must be well informed about the property's use and potential, including both its defects and its advantages.

► A reasonable time must be allowed for exposure in the open market.

► Payment must be made in cash or its equivalent.

► The price must represent a normal consideration for the property sold, unaffected by special financing amounts or terms, services, fees, costs, or credits incurred in the market transaction.

Market value versus market price.

Market value is an opinion of value based on an analysis of data. The data may include not only an analysis of comparable sales but also an analysis of potential income, expenses, and replacement costs (less any depreciation). Market price, on the other hand, is what a property actually sells for—its sales price. In theory, market price should be the same as market value. Market price can be taken as accurate evidence of current market value, however, only if the conditions essential to market value exist. Sometimes, property may be sold below market value—for instance, when the seller is forced to sell quickly or when a sale is arranged between relatives.

Market value versus cost.

An important distinction can be made between market value and cost. One of the most common misconceptions about valuing property is that cost represents market value. Cost and market value may be the same. In fact, when the improvements on a property are new, cost and value are likely to be equal. But more often, cost does not equal market value. For example, a homeowner may install a swimming pool for $15,000; however, the cost of the improvement may not add $15,000 to the value of the property.

Basic Principles of Value

A number of economic principles can affect the value of real estate. The most important are defined in the text that follows.

Anticipation.

According to the principle of anticipation, value is created by the expectation that certain events will occur. Value can increase or decrease in anticipation of some future benefit or detriment. For instance, the value of a house may be affected if rumors circulate that an adjacent property may be converted to commercial use in the near future. If the property has been a vacant eyesore, it is possible that the neighboring home's value will increase. On the other hand, if the vacant property had been perceived as a park or playlot that added to the neighborhood's quiet atmosphere, the news of its replacement might cause the house's value to decline.

Change.

No physical or economic condition remains constant. This is the principle of change. Real estate is subject to natural phenomena such as tornadoes, fires, and routine wear and tear. The real estate business is subject to market demands, like any other business. An appraiser must be knowledgeable about both the past and, perhaps, the predictable future effects of natural phenomena and the behavior of the marketplace.

Competition.

Competition is the interaction of supply and demand. Excess profits tend to attract competition. For example, the success of a retail store may cause investors to open similar stores in the area. This tends to mean less profit for all stores concerned unless the purchasing power in the area increases substantially.

Conformity.

The principle of conformity says that value is created when a property is in harmony with its surroundings. Maximum value is realized if the use of land conforms to existing neighborhood standards. In single-family residential neighborhoods, for instance, buildings should be similar in design, construction, size, and age.

Contribution.

Under the principle of contribution, the value of any part of a property is measured by its effect on the value of the whole. Installing a swimming pool, greenhouse, or private bowling alley may not add value to the property equal to the cost. On the other hand, remodeling an outdated kitchen or bathroom probably would.

Highest and best use.

The most profitable single use to which a property may be put, or the use that is most likely to be in demand in the near future, is the property's highest and best use. The use must be

► legally permitted,

► financially feasible,

► physically possible, and

► maximally productive.

The highest and best use of a site can change with social, political, and economic forces. For instance, a parking lot in a busy downtown area may not maximize the land's profitability to the same extent an office building might. Highest and best use is noted in every appraisal.

Increasing and diminishing returns.

The addition of improvements to land and structures increases value only to the assets' maximum value. Beyond that point, additional improvements no longer affect a property's value. As long as money spent on improvements produces an increase in income or value, the law of increasing returns applies. At the point where additional improvements do not increase income or value, the law of diminishing returns applies. No matter how much money is spent on the property, the property's value does not keep pace with the expenditures. For instance, a remodeled kitchen or bathroom might increase the value of a house; adding restaurant-quality appliances and gold faucets, however, would be an investment that the owner probably would not be able to recover.

Plottage.

The principle of plottage holds that merging or consolidating adjacent lots into a single larger one produces a greater total land value than the sum of the two sites valued separately. For example, two adjacent lots valued at $35,000 each might have a combined value of $90,000 if consolidated. The process of merging two separately owned lots under one owner is known as assemblage. Plottage is the amount value is increased by successful assemblage.

Regression and progression.

In general, the worth of a better-quality property is adversely affected by the presence of a lesser-quality property. This is known as the principle of regression. Thus, in a neighborhood of modest homes, a structure that is larger, better maintained, or more luxurious would tend to be valued in the same range as the less lavish homes. Conversely, under the principle of progression, the value of a modest home would be higher if it were located among larger, fancier properties.

Substitution.

The principle of substitution says that the maximum value of a property tends to be set by how much it would cost to purchase an equally desirable and valuable substitute property.

Supply and demand.

The principle of supply and demand says that the value of a property depends on the number of properties available in the marketplace—the supply of the product. Other factors include the prices of other properties, the number of prospective purchasers, and the price buyers will pay.

THE THREE APPROACHES TO VALUE

To arrive at an accurate estimate of value, appraisers traditionally use three basic valuation techniques: the sales comparison approach, the cost approach, and the income approach. The three methods serve as checks against each other. Using them narrows the range within which the final estimate of value falls. Each method is generally considered most reliable for specific types of property.

The Sales Comparison Approach

In the sales comparison approach (also known as the market data approach), an estimate of value is obtained by comparing the property being appraised (the subject property) with recently sold comparable properties (properties similar to the subject). Because no two parcels of real estate are exactly alike, each comparable property must be analyzed for differences and similarities between it and the subject property. This approach is a good example of the principle of substitution, discussed above. The sales prices of the comparables must be adjusted for any dissimilarities. The principal factors for which adjustments must be made include the following:

► Property rights. An adjustment must be made when less than fee simple, the full legal bundle of rights, is involved. This includes land leases, ground rents, life estates, easements, deed restrictions, and encroachments.

► Financing concessions. The financing terms must be considered, including adjustments for differences such as mortgage loan terms and owner financing.

► Conditions of sale. Adjustments must be made for motivational factors that would affect the sale, such as foreclosure, a sale between family members, or some nonmonetary incentive.

► Date of sale. An adjustment must be made if economic changes occur between the date of sale of the comparable property and the date of the appraisal.

► Location. Similar properties might differ in price from neighborhood to

neighborhood or even between locations within the same neighborhood.

► Physical features and amenities. Physical features, such as the structure's age, size, and condition, may require adjustments.

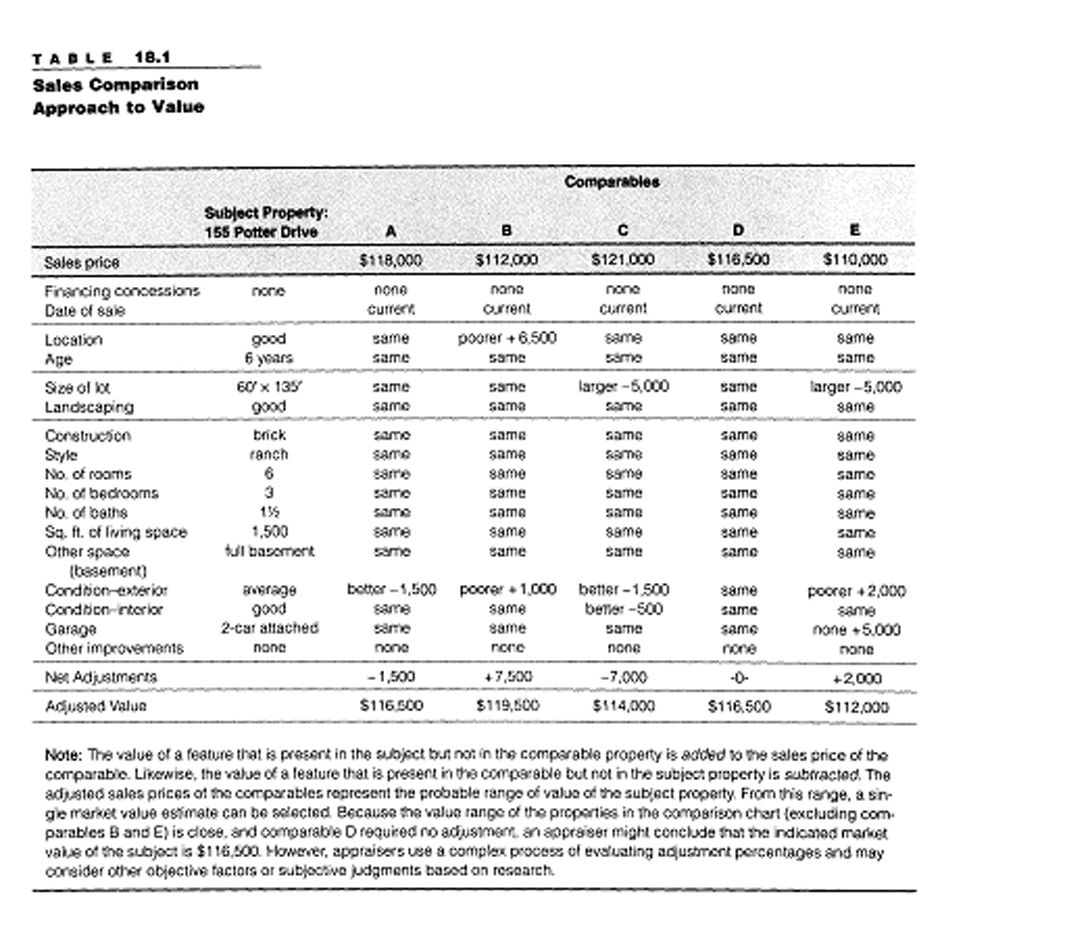

The sales comparison approach is considered the most reliable of the three approaches in appraising single-family homes, where the intangible benefits may be difficult to measure otherwise. Most appraisals include a minimum of three comparable sales reflective of the subject property. An example of the sales comparison approach is shown in Table 18.1.

The Cost Approach

The cost approach to value also is based on the principle of substitution. The cost approach consists of five steps:

1) Estimate the value of the land as if it were vacant and available to be put to its highest and best use. (Note that the value of the land is not subject to depreciation.)

2) Estimate the current cost of constructing buildings and improvements.

3) Estimate the amount of accrued depreciation resulting from the property's physical deterioration, functional obsolescence, and external depreciation.

4) Deduct the accrued depreciation (Step 3) from the construction cost (Step 2).

5) Add the estimated land value (Step 1) to the depreciated cost of the building and site improvements (Step 4) to arrive at the total property value.

FOR EXAMPLE

Value of the land = $25,000

Current cost of construction = $85,000

Accrued depreciation = $10,000

$85,000 - $10,000 = $75,000

$25,000 + $75,000 = $100,000

In this example, the total property value is $100,000.

There are two ways to look at the construction cost of a building for appraisal purposes: reproduction cost and replacement cost. Reproduction cost is the construction cost at current prices of an exact duplicate of the subject improvement, including both the benefits and the drawbacks of the property. Replacement cost new is the cost to construct an improvement similar to the subject property using current construction methods and materials, but not necessarily an exact duplicate. Replacement cost new is more frequently used in appraising older structures because it eliminates obsolete features and takes advantage of current construction materials and techniques.

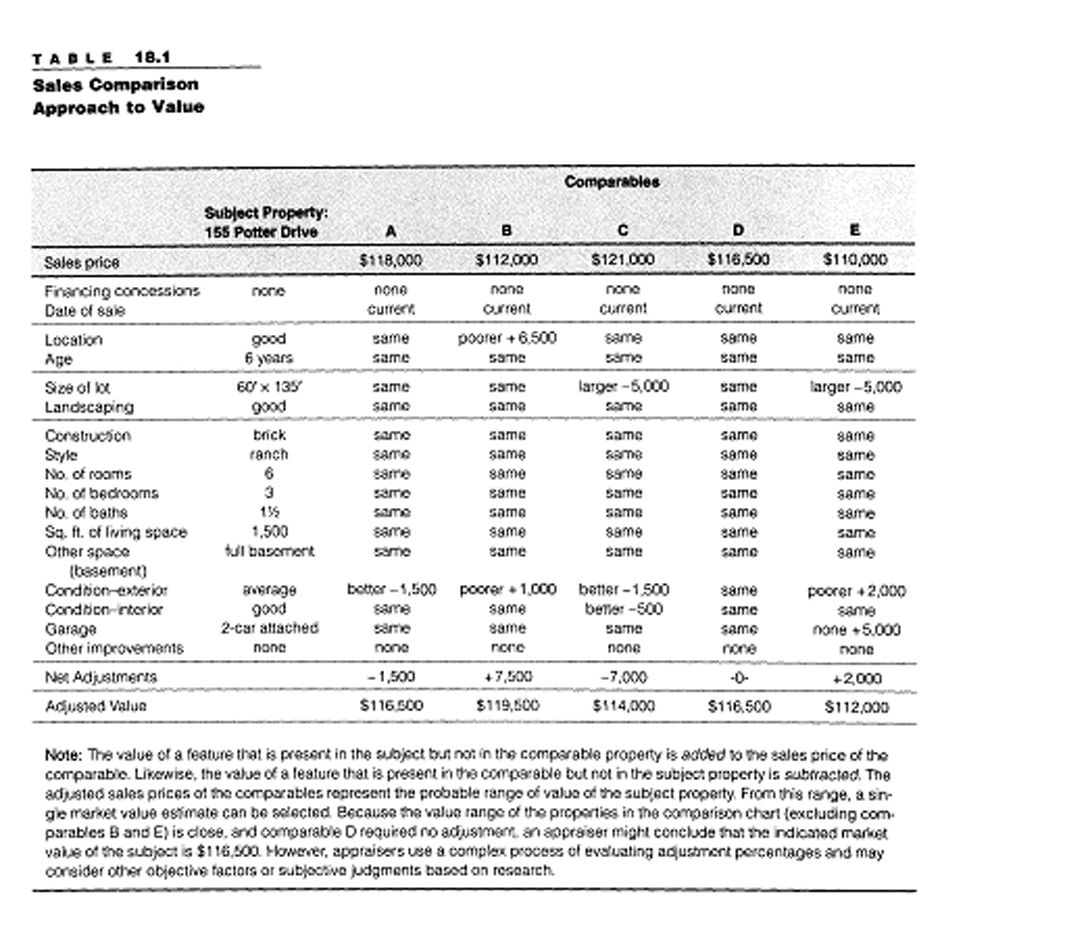

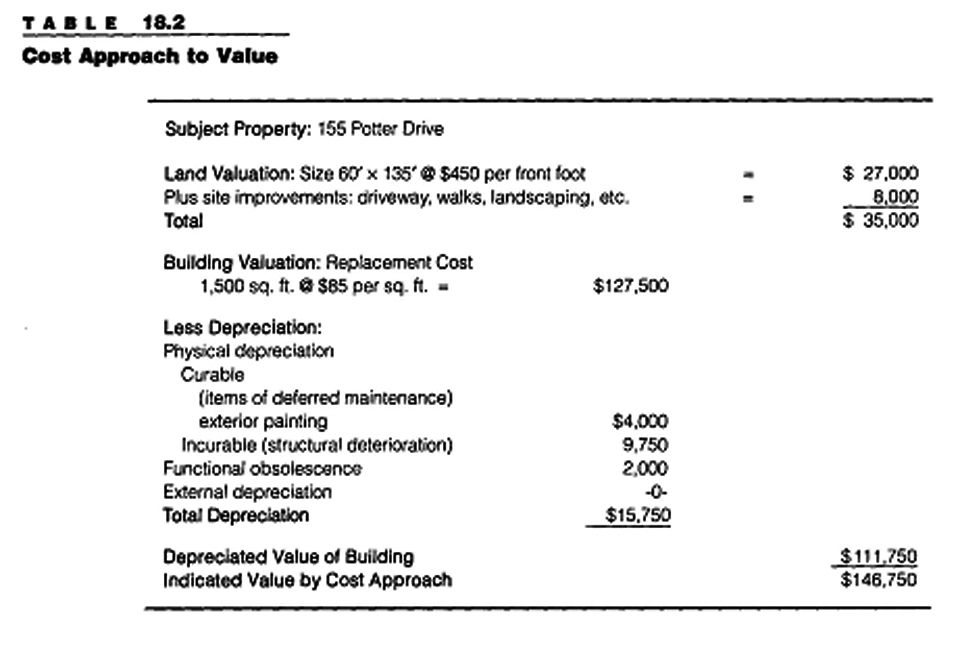

An example of the cost approach to value, applied to the same property as in Table 18.1, is shown in Table 18.2.

Determining reproduction or replacement cost new. An appraiser using the cost approach computes the reproduction or replacement cost of a building using one of the following four methods:

1) Square-foot method. The cost per square foot of a recently built comparable structure is multiplied by the number of square feet (using exterior dimensions) in the subject building. The square-foot method is the most common and easiest method of cost estimation. Table 18.2 uses the square-foot method, which is also referred to as the comparison method. For some (usually nonresidential) properties, the cost per cubic foot of a recently built comparable structure is multiplied by the number of cubic feet in the subject structure.

2) Unit-in-place method. In the unit-in-place method, the replacement cost of a structure is estimated based on the construction cost per unit of measure of individual building components, including material, labor, overhead, and builder's profit. Most components are measured in square feet, although items such as plumbing fixtures are estimated by cost. The sum of the components is the cost of the new structure.

3) Quantity-survey method. The quantity and quality of all materials (such as lumber, brick, and plaster) and the labor are estimated on a unit cost basis. These factors are added to indirect costs (for example, building permit, survey, payroll, taxes, and builder's profit) to arrive at the total cost of the structure. Because it is so detailed and time-consuming, the quantity-survey method is usually used only in appraising historical properties. It is, however, the most accurate method of appraising new construction.

4) Index method. A factor representing the percentage increase of construction costs up to the present time is applied to the original cost of the subject property. Because it fails to take into account individual property variables, the index method is useful only as a check of the estimate reached by one of the other methods.

Depreciation.

In a real estate appraisal, depreciation is a loss in value due to any cause. It refers to a condition that adversely affects the value of an improvement to real property. Remember: Land does not depreciate—it retains its value indefinitely, except in such rare cases as down-zoned urban parcels, improperly developed land, or misused farmland.

Depreciation is considered to be curable or incurable, depending on the contribution of the expenditure to the value of the property. For appraisal purposes (as opposed to depreciation for tax purposes, discussed in Appendix 1), depreciation is divided into three classes, according to its cause:

1) Physical deterioration. Curable: an item in need of repair, such as painting (deferred maintenance), that is economically feasible and would result in an increase in value equal to or exceeding the cost. Incurable: a defect caused by physical wear and tear if its correction would not be economically feasible or contribute a comparable value to the building. The cost of a major repair may not warrant the financial investment.

2) Functional obsolescence. Curable: outmoded or unacceptable physical or design features that are no longer considered desirable by purchasers. Such features, however, could be replaced or redesigned at a cost that would be offset by the anticipated increase in ultimate value. Outmoded plumbing, for instance, is usually easily replaced. Room function may be redefined at no cost if the basic room layout allows for it. A bedroom adjacent to a kitchen, for example, may be converted to a family room. Incurable: currently undesirable physical or design features that could not be easily remedied because the cost of cure would be greater than its resulting increase in value. An office building that cannot be economically air-conditioned, for example, suffers from incurable functional obsolescence if the cost of adding air-conditioning is greater than its contribution to the building's value.

3) External obsolescence. Incurable: caused by negative factors not on the subject property, such as environmental, social, or economic forces. This type of depreciation is always incurable. The loss in value cannot be reversed by spending money on the property. For example, proximity to a nuisance, such as a polluting factory or a deteriorating neighborhood, is one factor that could not be cured by the owner of the subject property.

The easiest but least precise way to determine depreciation is the straight-line method, also called the economic age-life method. Depreciation is assumed to occur at an even rate over a structure's economic life, the period during which it is expected to remain useful for its original intended purpose. The property's cost is divided by the number of years of its expected economic life to derive the amount of annual depreciation.

For instance, a $120,000 property may have a land value of $30,000 and an improvement value of $90,000. If the improvement is expected to last 60 years, the annual straight-line depreciation would be $1,500 ($90,000 divided by 60 years). Such depreciation can be calculated as an annual dollar amount or as a percentage of a property's improvements.

The cost approach is most helpful in the appraisal of newer or special-purpose buildings such as schools, churches, and public buildings. Such properties are difficult to appraise using other methods because there are seldom enough local sales to use as comparables and because the properties do not ordinarily generate income.

Much of the functional obsolescence and all of the external depreciation can be evaluated only by considering the actions of buyers in the marketplace.

The Income Approach

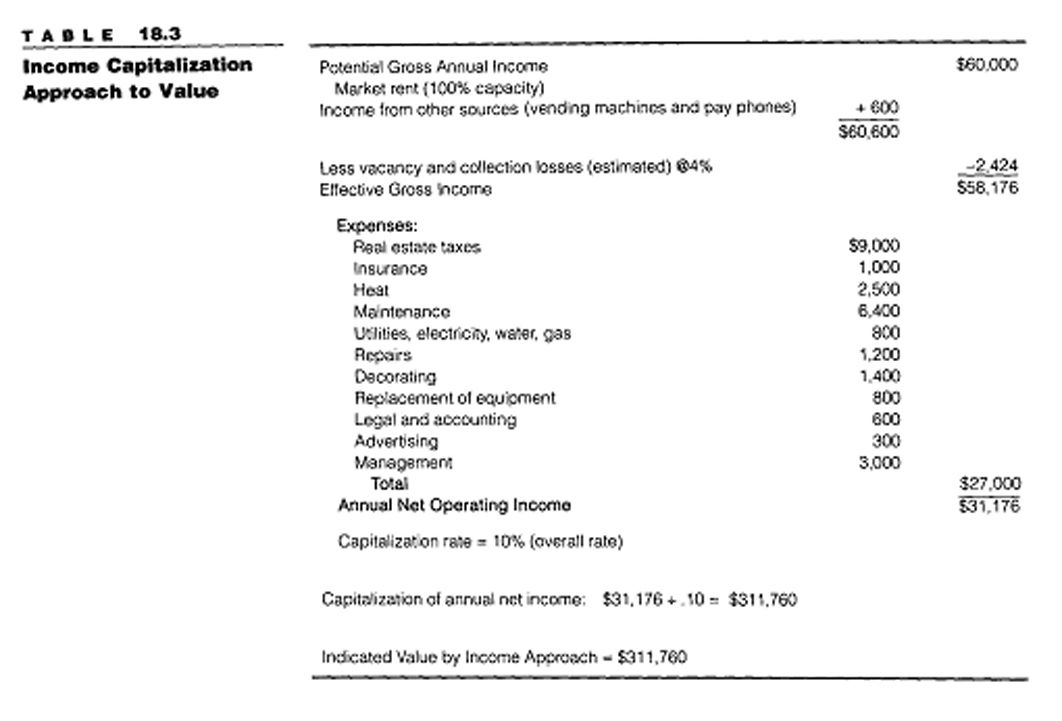

The income approach to value is based on the present value of the rights to future income. It assumes that the income generated by a property will determine the property's value. The income approach is used for valuation of income-producing properties such as apartment buildings, office buildings, and shopping centers. In estimating value using the income approach, an appraiser must take the following five steps, illustrated in Table 18.3.

1) Estimate annual potential gross income. An estimate of economic rental income must be made based on market studies. Current rental income may not reflect the current market rental rates, especially in the case of short-term leases or leases about to terminate. Potential income includes other income to the property from such sources as vending machines, parking fees and laundry machines.

2) Deduct an appropriate allowance for vacancy and rent loss, based on the appraiser's experience, and arrive at the effective gross income.

3) Deduct the annual operating expenses, enumerated in Table 18.3, from the effective gross income to arrive at the annual net operating income (NOI). Management costs are always included, even if the current owner manages the property. Mortgage payments (principal and interest) are debt service and are not considered operating expenses. Also, capital expenditures are not considered expenses; however, an allowance can be calculated representing the annual usage of each major capital item.

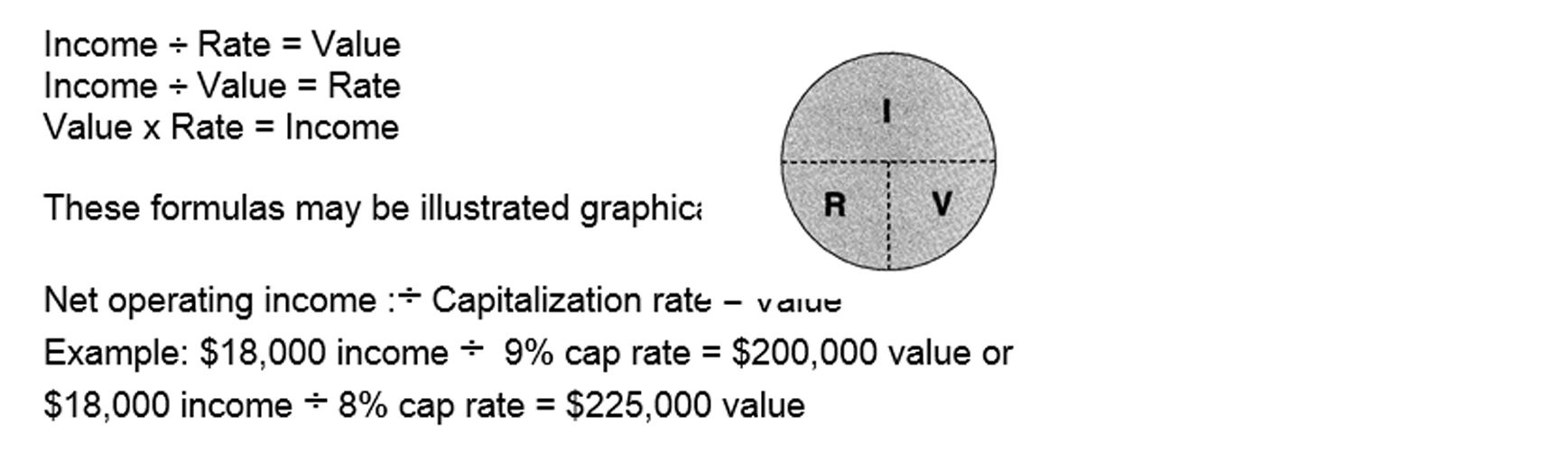

4) Estimate the price a typical investor would pay for the income produced by this particular type and class of property. This is done by estimating the rate of return (or yield) that an investor will demand for the investment of capital in this type of building. This rate of return is called the capitalization (or "cap") rate and is determined by comparing the relationship of net operating income with the sales prices of similar properties that have sold in the current market. For example, a comparable property that is producing an annual net income of $15,000 is sold for $187,500. The capitalization rate is $15,000 divided by $187,500, or 8 percent. If other comparable properties sold at prices that yielded substantially the same rate, it may be concluded that 8 percent is the rate that the appraiser should apply to the subject property.

5) Apply the capitalization rate to the property's annual net operating income to arrive at the estimate of the property's value.

With the appropriate capitalization rate and the projected annual net operating income, the appraiser can obtain an indication of value by the income approach.

This formula and its variations are important in dealing with income property:

Note the relationship between the rate and value. As the rate goes down, the value increases.

A very simplified version of the computations used in applying the income approach is illustrated in Table 18.3.

Gross rent or gross income multipliers.

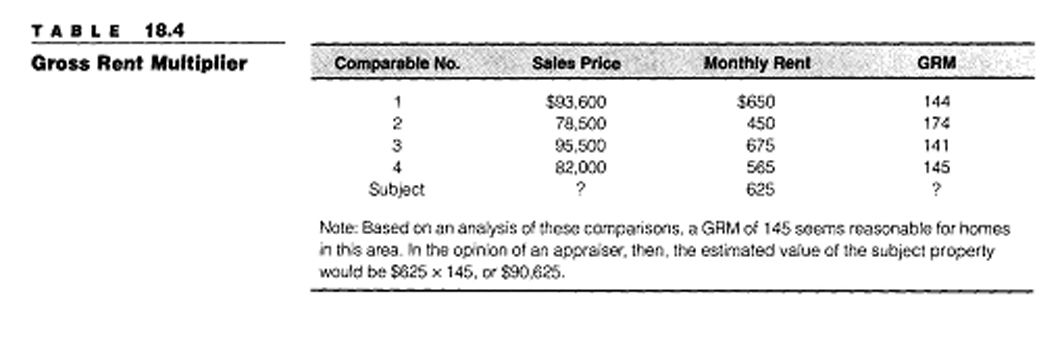

Certain properties, such as single family homes and two-unit buildings, are not purchased primarily for income. As a substitute for a more elaborate income capitalization analysis, the gross rent multiplier (GRM) and gross income multiplier (GIM) are often used in the appraisal process. Each relates the sales price of a property to its rental income.

Because single-family residences usually produce only rental incomes, the gross rent multiplier is used. This relates a sales price to monthly rental income. However, commercial and industrial properties generate income from many other sources (rent, concessions, escalator clause income, and so forth), and they are valued using their annual income from all sources.

The formulas are as follows:

1) For five or more residential units, commercial or industrial property: Sales price ÷ Gross Income = Gross Income Multiplier (GIM) -----or

2) For one to four residential units: Sales price ÷ Gross Rent = Gross Rent Multiplier (GRM)

For example, if a home recently sold for $82,000 and its monthly rental income was $650, the GRM for the property would be computed $82,000 ÷ $650 = 126.2 GRM

To establish an accurate GRM, an appraiser must have recent sales and rental data from at least four properties that are similar to the subject property. The resulting GRM can then be applied to the estimated fair market rental of the subject property to arrive at its market value. The formula would be

Rental income x GRM = Estimated market value. Table 18.4 shows some examples of GRM comparisons.

Reconciliation

When the three approaches to value are applied to the same property, they normally produce three separate indications of value. (For instance, compare Table 18.1 with Table 18.2.) Reconciliation is the art of analyzing and effectively weighing the findings from the three approaches.

The process of reconciliation is not simply taking the average of the three estimates of value. An average implies that the data and logic applied in each of the approaches are equally valid and reliable and should therefore be given equal weight. In fact, however, certain approaches are more valid and reliable with some kinds of properties than with others.

For example, in appraising a home, the income approach is rarely valid, and the cost approach is of limited value unless the home is relatively new. Therefore, the sales comparison approach is usually given greatest weight in valuing single-family residences. In the appraisal of income or investment property, the income approach normally is given the greatest weight. In the appraisal of churches, libraries, museums, schools, and other special-use properties, where little or no income or sales revenue is generated, the cost approach usually is assigned the greatest weight. From this analysis, or reconciliation, a single estimate of market value is produced.

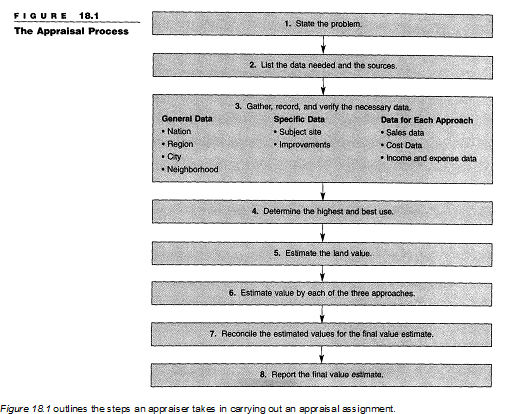

THE APPRAISAL PROCESS

Although appraising is not an exact or a precise science, the key to an accurate appraisal lies in the methodical collection and analysis of data. The appraisal process is an orderly set of procedures used to collect and analyze data to arrive at an ultimate value conclusion. The data are divided into two basic classes:

1) General data, covering the nation, region, city, and neighborhood. Of particular importance is the neighborhood, where an appraiser finds the physical, economic, social, and political influences that directly affect the value and potential of the subject property.

2) Specific data, covering details of the subject property as well as comparative data relating to costs, sales, income, and expenses of properties similar to and competitive with the subject property.

Once the approaches have been reconciled and an opinion of value has been reached, the appraiser prepares a report for the client. The report should

► identify the real estate and real property interest being appraised;

► state the purpose and intended use of the appraisal;

► define the value to be estimated;

state the effective date of the value and the date of the report;

► state the extent of the process of collecting, confirming, and reporting the data;

► list all assumptions and limiting conditions that affect the analysis, opinion, and conclusions of value;

► describe the information considered, the appraisal procedures followed, and the reasoning that supports the report's conclusions (if an approach was excluded, the report should explain why);

► describe (if necessary or appropriate) the appraiser's opinion of the highest and best use of the real estate;

► describe any additional information that may be appropriate to show compliance with the specific guidelines established in the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP) or to clearly identify and explain any departures from these guidelines; and

► include a signed certification, as required by the Uniform Standards.

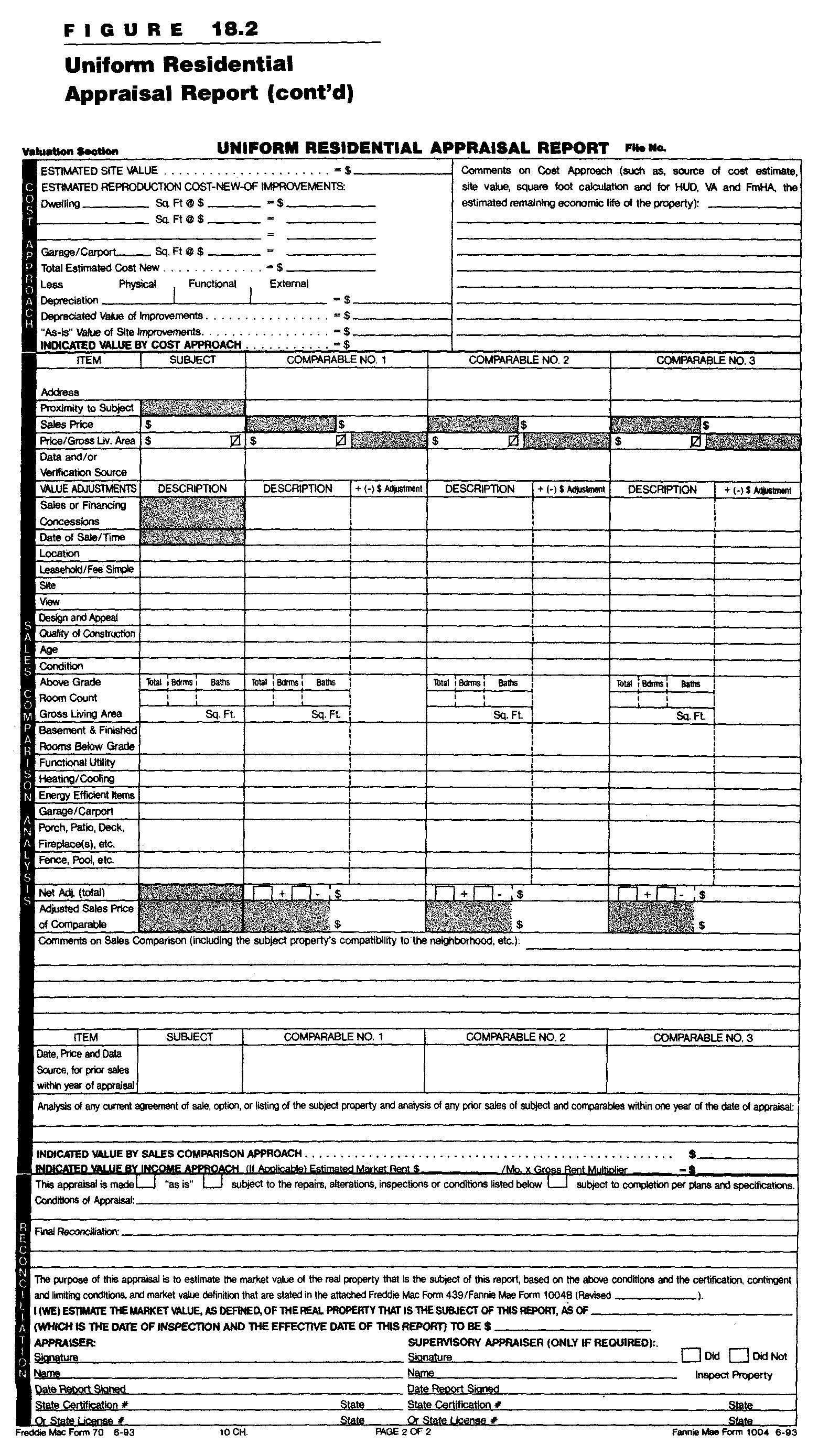

Figure 18.2 shows the Uniform Residential Appraisal Report, the form required by many government agencies. It illustrates the types of detailed information required of an appraisal of residential property.

IN PRACTICE The role of an appraiser is not to determine value. Rather, an appraiser develops a supportable and objective report about the value of the subject property. The appraiser relies on experience and expertise in valuation theories to evaluate market data. The appraiser does not establish the property's worth; instead, he or she verifies what the market indicates. This is important to remember, particularly when dealing with a property owner who may lack objectivity about the realistic value of his or her property. The lack of objectivity also can complicate a salesperson's ability to list the property within the most probable range of market value. However, there are inherent conflicts between the appraiser's role and the real estate agent's and seller's roles. The agent and seller are seeking maximum value while looking ahead to the future. The appraiser, on the other hand, is seeking to justify the appraisal by looking at past events.

SUMMARY

To appraise real estate means to estimate its value. Although many types of value exist, the most common objective of an appraisal is to estimate market value—the most probable sales price of a property. Basic to appraising are certain underlying economic principles, such as highest and best use, substitution, supply and demand, conformity, anticipation, increasing and diminishing returns, regression, progression, plottage, contribution, competition, and change.

Appraisals are concerned with values, prices, and costs. It is vital to understand the distinctions among these terms. Value is an estimate of future benefits, cost represents a measure of past expenditures, and price reflects the actual amount of money paid for a property.

A professional appraiser analyzes a property through three approaches to value. In the sales comparison approach, the value of the subject property is compared with the values of others like it that have sold recently. Because no two properties are exactly alike, adjustments must be made to account for any differences. With the cost approach, an appraiser calculates the cost of building a similar structure on a similar site. The appraiser then subtracts depreciation (losses in value), which reflects the differences between new properties of this type and

the present condition of the subject property. The income approach is an analysis based on the relationship between the rate of return that an investor requires and the net income that a property produces.

An informal version of the income approach, called the gross rent multiplier (GRM), may be used to estimate the value of single-family residential properties that are not usually rented, but could be. The GRM is computed by dividing the sales price of a property by its gross monthly rent. For commercial or industrial property, a gross income multiplier (GIM), based on annual income from all sources, may be used.

Normally, the application of the three approaches results in three different estimates of value. In the process of reconciliation, the validity and reliability of each approach are weighed objectively to arrive at the single best and most supportable estimate of value.

RELATED STATE OF TENNESSEE LAWS, RULES, and REGULATIONS

FAQ’s about Related Real Estate Activities

Do appraisers have to be licensed in Tennessee?

Tennessee law requires that all appraisals be performed by licensed or certified appraisers, without exception. The law creates three categories of appraisers: Licensed Appraiser, Certified Residential Appraiser, and Certified General Appraiser.

What are Tennessee state requirements for a licensed appraiser?

A Licensed Appraiser must satisfactorily complete a total of 90 hours of classroom instruction including 15 hours of training in the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP) and 30 hours of basic appraisal principles.

The person desiring to become a Licensed Appraiser must also have two years of experience and a minimum of 2,000 hours of experience as a registered trainee. This experience must be obtained while the trainee is under the supervision of a Certified (Residential/General) Appraiser. The requirements also include an interview with members of the Tennessee Real Estate Appraiser Commission and passing an examination.

A Licensed Appraiser is allowed to appraise one- to four-family residential properties up to a value of $1 million and nonresidential properties up to a value of $250,000.

What are Tennessee state requirements for a Certified Residential Appraiser?

The majority of appraisers in Tennessee are Certified Residential Appraisers. They have completed 120 classroom hours, including the 15-hour course in USPAP They have also satisfied an experience requirement of two years and 2,500 hours, again under the supervision of a certified appraiser. The requirements also include an interview with members of the Tennessee Real Estate Appraiser Commission and passing an examination.

The Certified Residential Appraiser can appraise one to four-family residential properties without limit on value and nonresidential property only up to a value of $250,000.

What are Tennessee state requirements for a Certified General Appraiser?

The highest level of appraiser certification is the Certified General Appraiser. This requires 180 classroom hours, including the USPAP course and a 30hour course in the principles of capitalization.

Additionally, the person desiring the Certified General Appraiser classification must have 30 months of experience and 3,000 hours of experience under a certified appraiser, of which 1,500 or more hours must be in nonresidential appraising. Again, the applicant must undergo an interview with the appraiser commission and pass anexamination.

There is no limitation imposed on the Certified General Appraiser's practice, insofar as value limits or property types are concerned.

Are there any other requirements?

Tennessee requires that an applicant first become a trainee registered with the state before the experience requirements can begin. To become a trainee, the applicant must have completed 45 hours of education, including a 15-hour class in Uniform Standards and the 30-hour class in the basic principles of appraising.

Only a Certified Residential Appraiser or a Certified General Appraiser can supervise trainees in Tennessee. A Licensed Appraiser may not supervise trainees.

Do home inspectors have to be licensed?

Yes. To become a licensed home inspector in Tennessee, you must successfully complete a 90-hour pre-licensing course approved by the Tennessee Department of Commerce and Insurance, pass the National Home Inspector Exam, and carry liability insurance.