CHAPTER NINETEEN

LAND-USE CONTROLS AND PROPERTY DEVELOPMENT

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

When you've finished reading this Chapter, you should be able to:

► identify the various types of public and private land-use controls.

► describe how a comprehensive plan influences local real estate development.

► explain the various issues involved in subdivision.

► distinguish the function and characteristics of building codes and zoning ordinances.

►define the following terms: buffer zone; building code certificate of occupancy; comprehensive plan; conditional-use permit; covenants, conditions, and restrictions (CC&Rs); density zoning; developer; enabling acts; Interstate Land Sales Full Disclosure Act; inverse condemnation; nonconforming use; planned unit development (PUD); plat; restrictive covenants; subdivider; subdivision; variance; zoning; and zoning ordinance.

REAL ESTATE PRACTICE & PRINCIPLES KEY WORD MATCH QUIZ

--- CLICK HERE ---

I would encourage you to take this “Match quiz” now as a pre-chapter challenge to see how many of these key words or phrases you are familiar with. At the end of each chapter I recommend that you take the quiz again to reinforce these important keywords. Each page contains four words or phrases and you need to drag and drop the correct definition into the puzzle key. Each page is considered as a question, but there is no scoring and you can return to each chapter quiz as many times as needed to reinforce your memory.

WHY LEARN ABOUT... LAND-USE CONT ROLS AND PROPERTY DEVELOPMENT?

A client comes to your office, wanting to buy a property for a specific commercial or residential development use. If you are familiar with land-use and property development issues, you will be able to show the client appropriate properties that can be lawfully developed according to the client's plans. If you aren't familiar with these concepts, it will be easy to erroneously assume that any development is legal any-where or that because neighboring properties have been developed in a certain way, a vacant property can be developed the same way. Real estate agents have been successfully sued by buyers who discovered after a sale was closed that their intended use for their new property was prohibited by local law or private restriction. Understanding land-use controls and property development is important for your involvement in real estate.

LAND-USE CONTROLS

Land use is controlled and regulated through public and private restrictions and through the direct ownership of land by federal, state, and local governments. Over the years, the government's policy has been to encourage private ownership of land.

Home ownership is often referred to as the American Dream. It is necessary, however, for a certain amount of land to be owned by the government for such uses as municipal buildings, state legislative houses, schools, and military stations. Government ownership may also serve the public interest through urban renewal efforts, public housing, and streets and highways. Often, the only way to ensure that enough land is set aside for recreational and conservation purposes is through direct government ownership in the form of national and state parks and forest preserves. Beyond this sort of direct ownership of land, however, most government controls on property occur at the local level.

The states' police power is their inherent authority to create regulations needed to protect the public health, safety, and welfare. The states delegate to counties and local municipalities the authority to enact ordinances in keeping with general laws. The increasing demands placed on finite natural resources have made it necessary for cities, towns, and villages to increase their limitations on the private use of real estate. There are now controls over noise, air, and water pollution as well as population density.

THE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN

Local governments establish development goals by creating a comprehensive plan. This is also referred to as a master plan. Municipalities and counties develop plans to control growth and development. Each plan includes the municipality's (or other government body's) objectives for the future and the strategies and timing for those objectives to be implemented. For instance, a community may want to ensure that social and economic needs are balanced with environmental and aesthetic concerns. The comprehensive plan usually includes the following basic elements:

► Land use, that is, a determination of how much land may be proposed for residence, industry, business, agriculture, traffic and transit facilities, utilities, community facilities, parks and recreational facilities, floodplains, and areas of special hazards

► Housing needs of present and anticipated residents, including rehabilitation

of declining neighborhoods as well as new residential developments

► Movement of people and goods, including highways and public transit, park

ing facilities, and pedestrian and bikeway systems

► Community facilities and utilities such as schools, libraries, hospitals, recreational facilities, fire and police stations, water resources, sewerage, waste treatment and disposal, storm drainage, and flood management

► Energy conservation to reduce energy consumption and promote the use of renewable energy sources

The preparation of a comprehensive plan involves surveys, studies, and analyses of housing, demographic, and economic characteristics and trends. The municipality's planning activities may be coordinated with other government bodies and private interests to achieve orderly growth and development.

FOR EXAMPLE After the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 reduced most of the city's downtown to rubble and ash, the city engaged planner Daniel Burnham to lay out a design for Chicago's future. The resulting Burnham Plan of orderly boulevards linking a park along Lake Michigan with other large parks and public spaces throughout the city established an ideal urban space. The plan is still being implemented today.

ZONING

Zoning ordinances are local laws that implement the comprehensive plan and regulate and control the use of land and structures within designated land-use districts. If the comprehensive plan is the big picture, zoning is the details. Zoning affects such things as

► permitted uses of each parcel of land,

► lot sizes,

► types of structures,

► building heights,

► setbacks (the minimum distance away from streets or sidewalks that structures may be built),

► style and appearance of structures,

► density (the ratio of land area to structure area), and

► protection of natural resources.

Zoning ordinances cannot be static; they must remain flexible to meet the changing needs of society.

FOR EXAMPLE In many large cities, factories and warehouses sit empty. Some cities have begun changing the zoning ordinances for such properties to permit new residential or commercial developments in areas once zoned strictly for heavy industrial use. Coupled with tax incentives, the changes lure developers back into the cities. The resulting housing is modern, conveniently located, and affordable. Simple zoning changes can help revitalize whole neighborhoods in big cities.

No nationwide or statewide zoning ordinances exist. Rather, zoning powers are conferred on municipal governments by state enabling acts. State and federal governments may, however, regulate land use through special legislation such as scenic easement, coastal management, and environmental laws.

Zoning Objectives

Zoning ordinances have traditionally classified land use into residential, commercial, industrial, and agricultural. These land-use areas are further divided into subclasses. For example, residential areas may be subdivided to provide for detached single-family dwellings, semidetached structures containing not more than four dwelling units, walkup apartments, highrise apartments, and so forth.

To meet both the growing demand for a variety of housing types and the need for innovative residential and nonresidential development, municipalities are adopting ordinances for subdivisions and planned residential developments. Some municipalities also use buffer zones, such as landscaped parks and play-grounds, to screen residential areas from nonresidential zones. Certain types of zoning that focus on special land-use objectives are used in some areas. These include

► bulk zoning to control density and avoid overcrowding by imposing restrictions such as setbacks, building heights, and percentage of open area or by restricting new construction projects;

► aesthetic zoning to specify certain types of architecture for new buildings; and

► incentive zoning to ensure that certain uses are incorporated into developments, such as requiring the street floor of an office building to house retail establishments.

Constitutional issues and zoning ordinances.

Zoning can be a highly controversial issue. Among other things, it often raises questions of constitutional law. The preamble of the U.S. Constitution provides for the promotion of the general welfare, but the Fourteenth Amendment prevents the states from depriving "any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law." How is a local government to enact zoning ordinances that protect public safety and welfare without violating the constitutional rights of property owners?

Any land-use legislation that is destructive, unreasonable, arbitrary, or confiscatory usually is considered void. Furthermore, zoning ordinances must not violate the various provisions of the constitution of the state in which the real estate is located. Tests commonly applied in determining the validity of ordinances require that the

► power be exercised in a reasonable manner;

► provisions be clear and specific;

► ordinances be nondiscriminatory;

► ordinances promote public health, safety, and general welfare under the police power concept; and

► ordinances apply to all property in a similar manner.

Taking.

The concept of taking comes from the takings clause of the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The clause reads, "nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation." This means that when land is taken for public use through the government's power of eminent domain or condemnation, the owner must be compensated. In general, no land is exempt from government seizure. The rule, however, is that the government cannot seize land without paying for it. This payment is referred to as just compensation—compensation that is just, or fair.

Inverse condemnation is an action brought by a property owner seeking just compensation for land taken for a public use where it appears that the taker of the property does not intend to bring eminent domain proceedings. The property is condemned because its use and value have been diminished due to an adjacent property's public use, such as an airport or highway. For example, property along a newly constructed highway may be inversely condemned. While the property itself was not used in constructing the highway, the property's value may be significantly diminished due to the construction of the highway close to the property. The property owner may bring an inverse condemnation action to be compensated for the loss.

It is sometimes very difficult to determine what level of compensation is fair in any particular situation. The compensation may be negotiated between the owner and the government, or the owner may seek a court judgment setting the amount.

IN PRACTICE One method used to determine just compensation is the before-and-after method. This method is used primarily where a portion of an owner's property is seized for public use. The value of the owner's remaining property after the taking is subtracted from the value of the whole parcel before the taking. The result is the total amount of compensation due to the owner.

Zoning Permits

Zoning laws are generally enforced through the use of permits. Compliance with zoning can be monitored by requiring that property owners obtain permits before they begin any development. A permit will not be issued unless a proposed development conforms to the permitted zoning, among other requirements. Zoning permits are usually required before building permits can be issued.

Zoning hearing board.

Zoning hearing boards (or zoning boards of appeal) have been established in most communities to hear testimony (positive and negative) about the effects a zoning ordinance may have on specific parcels of property. Petitions for variances or exceptions to the zoning law may be presented to an appeal board.

Nonconforming use.

Frequently, a lot or an improvement does not conform to the zoning use because it existed before the enactment or amendment of the zoning ordinance. Such a nonconforming use may be allowed to continue legally as long as it complies with the regulations governing nonconformities in the local ordinance, or until the improvement is destroyed or torn down, or until the current use is abandoned. If the nonconforming use is allowed to continue indefinitely, it is considered to be grandfathered into the new zoning.

FOR EXAMPLE Under Pleasantville's old zoning ordinances, the C&E Store was well within a commercial zone. When the zoning map was changed to accommodate an increased need for residential housing in Pleasantville, C&E was grandfathered into the new zoning; that is, it was allowed to continue its successful operations, even though it did not fit the new zoning rules.

Variances and conditional-use permits.

Each time a plan or zoning ordinance is enacted, some property owners are inconvenienced and want to change the use of their property. Generally, these owners may appeal for either a conditional-use permit or a variance to allow a use that does not meet current zoning requirements.

A conditional-use permit (also known as a special-use permit) usually is granted to a property owner to allow a special use of property that is defined as an allowable conditional use within that zone, such as a house of worship or day-care center in a residential district. For a conditional-use permit to be appropriate, the intended use must meet certain standards set by the municipality.

A variance, on the other hand, permits a landowner to use his or her property in a manner that is strictly prohibited by the existing zoning. Variances provide relief if zoning regulations deprive an owner of the reasonable use of his or her property. To qualify for a variance, the owner must demonstrate the unique circumstances that make the variance necessary. In addition, the owner must prove that he or she is harmed and burdened by the regulations. A variance might also be sought to provide relief if existing zoning regulations create a physical hardship for the development of a specific property. For example, if an owner's lot is level next to a road, but slopes steeply 30 feet away from the road, the zoning board may allow a variance so the owner can build closer to the road than the setback allows.

Both variances and conditional-use permits are issued by zoning boards only after public hearings. The neighbors of a proposed use must be given an opportunity to voice their opinions.

A property owner also can seek a change in the zoning classification of a parcel of real estate by obtaining an amendment to the district map or a zoning ordinance for that area, that is, the owner can attempt to have the zoning changed to accommodate his or her intended use of the property. The proposed amendment must be brought before a public hearing on the matter and approved by the governing body of the community.

BUILDING CODES AND CERTIFICATES OF OCCUPANCY

Most municipalities have enacted ordinances to specify construction standards that must be met when repairing or erecting buildings. These are called building codes, and they set the requirements for kinds of materials and standards of workmanship, sanitary equipment, electrical wiring, fire prevention, and the like.

A property owner who wants to build a structure or alter or repair an existing building usually must obtain a building permit. Through the permit requirement, municipal officials are made aware of new construction or alterations and can verify compliance with building codes and zoning ordinances. Inspectors will closely examine the plans and conduct periodic inspections of the work. Once the completed structure has been inspected and found satisfactory, the municipal inspector issues a certificate of occupancy or occupancy permit.

If the construction of a building or an alteration violates a deed restriction (discussed later in this Chapter), the issuance of a building permit will not cure this violation. A building permit is merely evidence of the applicant's compliance with municipal regulations.

Similarly, communities with historic districts, or those that are interested in maintaining a particular "look" or character, may have aesthetic ordinances. These laws require that all new construction or restorations be approved by a special board. The board ensures that the new structures will blend in with existing building styles. Owners of existing properties may need to obtain approval to have their homes painted or remodeled.

IN PRACTICE The subject of planning, zoning, and restricting the use of real estate is extremely technical, and the interpretation of the law is not always clear. Questions concerning any of these subjects in relation to real estate transactions should be referred to legal counsel. Furthermore, the landowner should be aware of the costs for various permits.

SUBDIVISION

Most communities have adopted subdivision and land development ordinances as part of their comprehensive plans. An ordinance includes provisions for submitting and processing subdivision plats. A major advantage of subdivision ordinances is that they encourage flexibility, economy, and ingenuity in the use of land. A subdivider is a person who buys undeveloped acreage and divides it into smaller lots for sale to individuals or developers or for the subdivider's own use. A developer (who may also be a subdivider) improves the land, constructs homes or other buildings on the lots, and sells them. Developing is generally a much more extensive activity than subdividing.

Regulation of Land Development

Just as no national zoning ordinance exists, no uniform planning and land development legislation affects the entire country. Laws governing subdividing and land planning are controlled by the state and local governing bodies where the land is located. Rules and regulations developed by government agencies have, however, provided certain minimum standards. Many local governments have established standards that are higher than the minimum standards.

Land development plan.

Before the actual subdividing can begin, the subdivider must go through the process of land planning. The resulting land development plan must comply with the municipality's comprehensive plan. Although comprehensive plans and zoning ordinances are not necessarily inflexible, a plan that requires them to be changed must undergo long, expensive, and frequently complicated hearings.

Plats.

From the land development and subdivision plans, the subdivider draws plats. A plat is a detailed map that illustrates the geographic boundaries of individual lots. It also shows the blocks, sections, streets, public easements, and monuments in the prospective subdivision. A plat also may include engineering data and restrictive covenants. The plats must be approved by the municipality before they can be recorded. (See Figure 9.11 in Chapter 9 for an example of a subdivision plat map.) A developer is often required to submit an environmental impact report with the application for subdivision approval. This report explains what effect the proposed development will have on the surrounding area.

Subdivision Plans

In plotting out a subdivision according to local planning and zoning controls, a subdivider usually determines the size as well as the location of the individual lots. The maximum or minimum size of a lot is generally regulated by local ordinances and must be considered carefully.

The land itself must be studied, usually in cooperation with a surveyor, so that the subdivision takes advantage of natural drainage and land contours. A subdivider should provide for utility easements as well as easements for water and sewer mains.

Most subdivisions are laid out by use of lots and blocks. An area of land is designated as a block, and the area making up this block is divided into lots.

One negative aspect of subdivision development is the potential for increased tax burdens on all residents, both inside and outside the subdivision. To protect local taxpayers against the costs of a heightened demand for public services, many local governments strictly regulate nearly all aspects of subdivision development.

Subdivision Density

Zoning ordinances control land use. Such control often includes minimum lot sizes and population density requirements for subdivisions and land developments. For example, a typical zoning restriction may set the minimum lot area on which a subdivider can build a single-family housing unit at 10,000 square feet. This means that the subdivider can build four houses per acre. Many zoning authorities now establish special density zoning standards for certain subdivisions. Density zoning ordinances restrict the average maximum number of houses per acre that may be built within a particular subdivision. If the area is density zoned at an average maximum of four houses per acre, for instance, the sub-divider may choose to cluster building lots to achieve an open effect. Regardless of lot size or number of units, the sub-divider will be consistent with the ordinance as long as the average number of units in the development remains at or below the maximum density. This average is called gross density.

Street patterns.

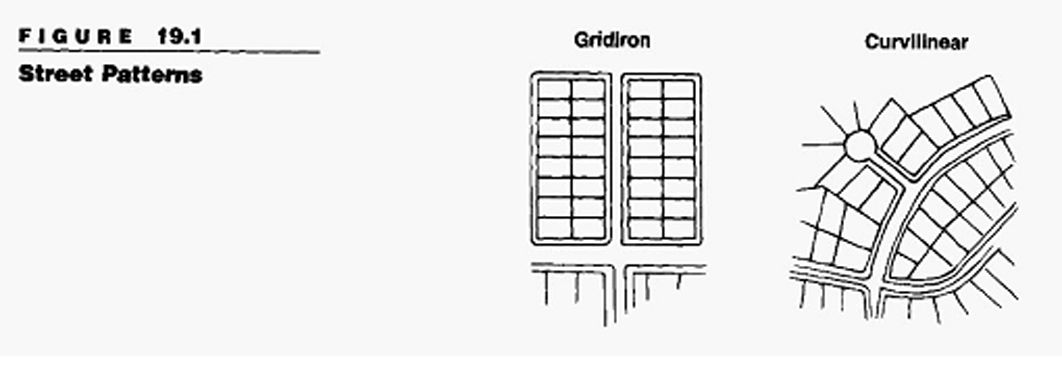

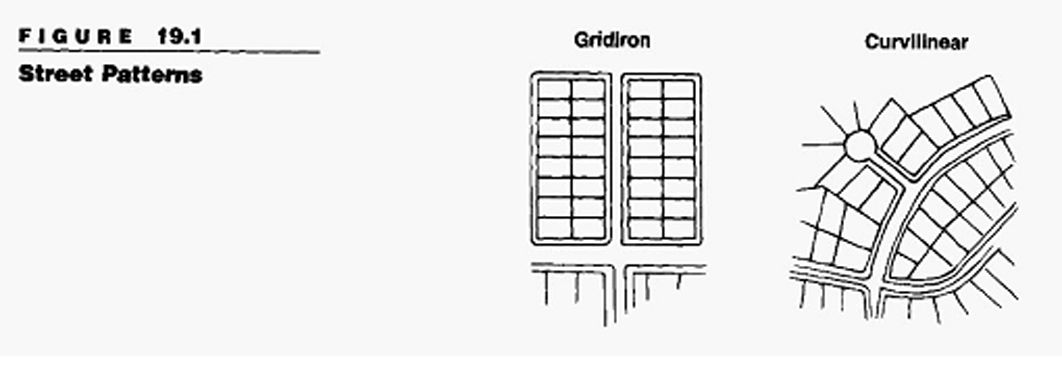

By varying street patterns and clustering housing units, a sub-divider can dramatically influence the amount of open or recreational space in a development. Two of these patterns are the gridiron and curvilinear patterns. (See Figure 19.1.)

The gridiron pattern evolved out of the government rectangular survey system. This pattern features large lots, wide streets, and limited-use service alleys. Sidewalks are usually adjacent to the streets or separated from them by narrow grassy areas. While the gridiron pattern provides for little open space and many lots may front on busy streets, it is an easy system to navigate.

The curvilinear system integrates major arteries of travel with smaller secondary and cul-de-sac streets carrying minor traffic. Curvilinear developments avoid the uniformity of the gridiron but often lack service alleys. The absence of straight-line travel and the lack of easy access tend to make curvilinear developments quieter and more secure. However, getting from place to place may be more challenging.

Clustering for open space.

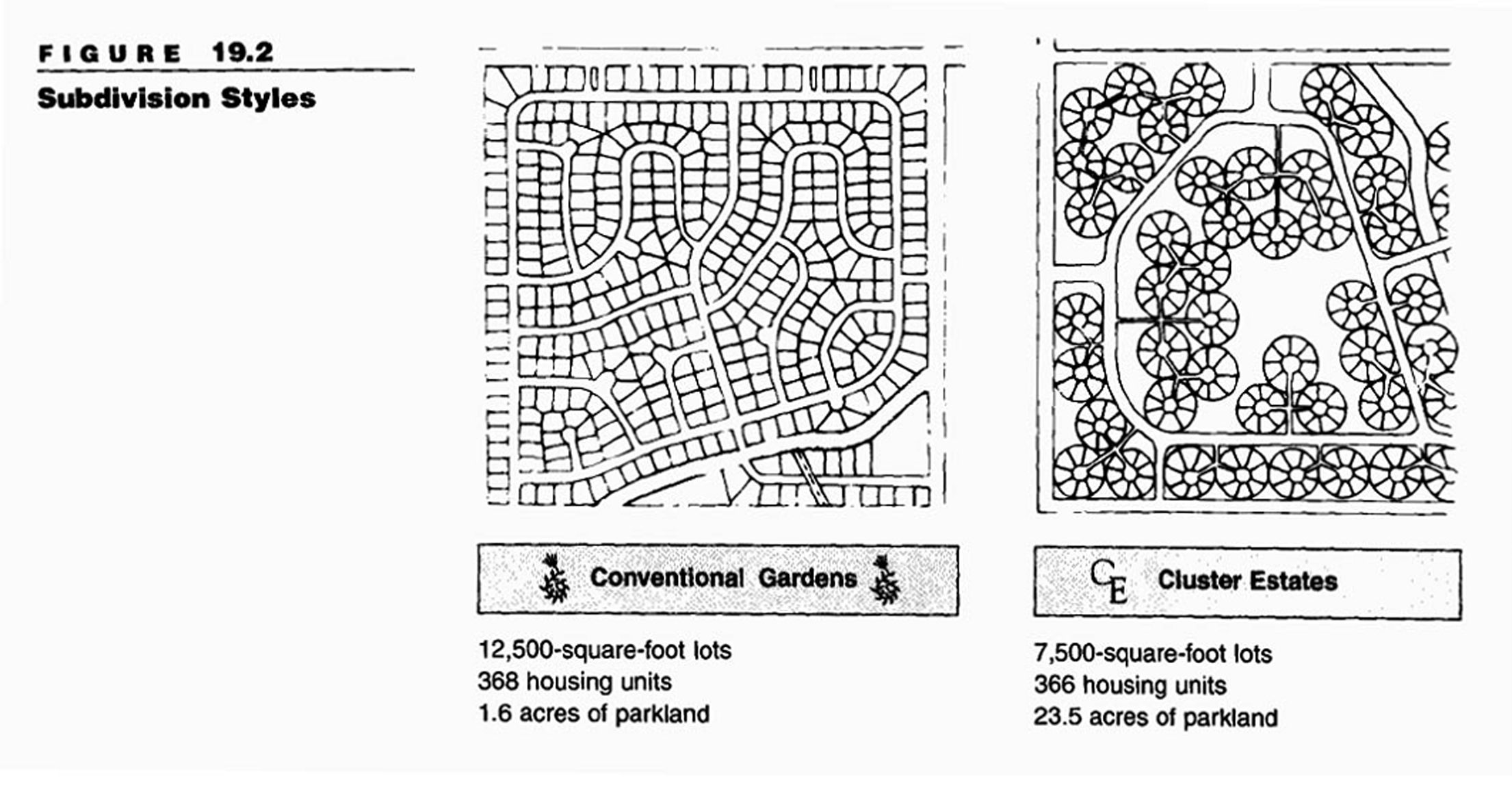

By slightly reducing lot sizes and clustering them around varying street patterns, a subdivider can house as many people in the same area as could be done using traditional subdividing plans but with substantially increased tracts of open space.

For example, compare the two subdivisions illustrated in Figure 19.2. Conventional Gardens is a conventionally designed subdivision containing 368 housing units. It uses 23,200 linear feet of street and leaves only 1.6 acres open for parkland. Contrast this with Cluster Estates. Both subdivisions are equal in size and terrain. But when lots are reduced in size and clustered around limited-access cul-de-sacs, the number of housing units remains nearly the same (366), with less street area (17,700 linear feet) and dramatically increased open space (23.5 acres). In addition, with modern building designs, this clustered plan could be modified to accommodate more than 1,000 town houses while retaining the attractive open spaces.

PRIVATE LAND-USE CONTROLS

Not all restrictions on the use of land are imposed by government bodies. Certain restrictions to control and to maintain the desirable quality and character of a property or subdivision may be created by private entities, including the property owners themselves. These restrictions are separate from and in addition to the land-use controls exercised by the government. No private restriction can violate a local, state, or federal law.

Restrictive covenants.

Restrictive covenants set standards for all the parcels within a defined subdivision. They usually govern the type, height, and size of buildings that individual owners can erect, as well as land use, architectural style, construction methods, setbacks, and square footage. The deed conveying a particular lot in the subdivision will refer to the plat or declaration of restrictions, thus limiting the title conveyed and binding all grantees. This is known as a deed restriction. Restrictions may have time limitations. A restriction might state that it is "effective for a period of 25 years from this date." After this time, it becomes inoperative. A time-limited covenant, however, may be extended by agreement.

Restrictive covenants are usually considered valid if they are reasonable restraints that benefit all property owners in the subdivision—for instance, to protect property values or safety. If, however, the terms of the restrictions are too broad, they will be construed as preventing the free transfer of property. If any restrictive covenant or condition is judged unenforceable by a court, the estate will stand free from the invalid covenant or condition. Restrictive covenants cannot be for illegal purposes, such as for the exclusion of members of certain races, nationalities, or religions.

Private land-use controls may be more restrictive of an owner's use than the local zoning ordinances. The rule is that the more restrictive of the two takes precedence.

Private restrictions can be enforced in court when one lot owner applies to the court for an injunction to prevent a neighboring lot owner from violating the recorded restrictions. The court injunction will direct the violator to stop or remove the violation. The court retains the power to punish the violator for failing to obey. If adjoining lot owners stand idly by while a violation is committed, they can lose the right to an injunction by their inaction. The court might claim their right was lost through lashes, that is, the legal principle that a right may be lost through undue delay or failure to assert it.

REGULATION OF LAND SALES

Just as the sale and use of property within a state are controlled by state and local governments, the sale of property in one state to buyers in another is subject to strict federal and state regulations.

Interstate Land Sales Full Disclosure Act

The federal Interstate Land Sales Full Disclosure Act regulates the interstate sale of unimproved lots. The act is administered by the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), through the office of Interstate Land Sales registration. It is designed to prevent fraudulent marketing schemes that may arise when land is sold without being seen by the purchasers. (You may be familiar with stories about gullible buyers whose land purchases were based on glossy brochures shown by smooth-talking salespersons. When the buyers finally went to visit the "little pieces of paradise" they'd bought, they frequently found worth-less swampland or barren desert.)

The act requires that developers file statements of record with HUD before they can offer unimproved lots in interstate commerce by telephone or through the mail. The statements of record must contain numerous disclosures about the properties.

Developers are also required to provide each purchaser or lessee of property with a printed report before the purchaser or lessee signs a purchase contract or lease. The report must disclose specific information about the land, including

► the type of title being transferred to the buyer,

► the number of homes currently occupied on the site,

► the availability of recreation facilities,

► the distance to nearby communities,

► utility services and charges, and

► soil conditions and foundation or construction problems.

If the purchaser or lessee does not receive a copy of the report before signing the purchase contract or lease, he or she may have grounds to void the contract.

The act provides a number of exemptions. For instance, it does not apply to subdivisions consisting of fewer than 25 lots or to those in which the lots are of 20 acres or more. Lots offered for sale solely to developers also are exempt from the act's requirements, as are lots on which buildings exist or where a seller is obligated to construct a building within two years.

State Subdivided-Land Sales Laws

Many state legislatures have enacted their own subdivided-land sales laws. Some affect only the sale of land located outside the state to state residents. Other states' laws regulate sales of land located both inside and outside the states. These state land sales laws tend to be stricter and more detailed than the federal law. Licensees should be aware of the laws in their states and how they compare with federal law.

SUMMARY

The control of land use is exercised through public controls, private (or non-government) controls, and direct public ownership of land.

Through power conferred by state enabling acts, local governments exercise public controls based on the states' police powers to protect the public health, safety, and welfare.

A comprehensive plan sets forth the development goals and objectives for the community. Zoning ordinances carrying out the provisions of the plan control the use of land and structures within designated land-use districts. Zoning enforcement problems involve zoning hearing boards, conditional-use permits, variances and exceptions, as well as nonconforming uses. Subdivision and land development regulations are adopted to maintain control of the development of expanding community areas so that growth is harmonious with community standards.

Building codes specify standards for construction, plumbing, sewers, electrical wiring, and equipment.

Public ownership is a means of land-use control that provides land for such public benefits as parks, highways, schools, and municipal buildings.

A subdivider buys undeveloped acreage, divides it into smaller parcels, and develops or sells it. A developer builds homes on the lots and sells them through the developer's own sales organization or through local real estate brokerage firms. City planners and land developers, working together, plan whole communities that are later incorporated into cities, towns, or villages.

Land development must comply with the master plans adopted by counties, cities, villages, or towns. This may entail approval of land-use plans by local planning committees or commissioners.

The process of subdivision includes dividing the tract of land into lots and blocks and providing for utility easements, as well as laying out street patterns

and widths. A subdivider must generally record a completed plat of subdivision, with all necessary approvals of public officials, in the county where the land is located. Subdividers usually place restrictions on the use of all lots in a subdivision as a general plan for the benefit of all lot owners.

By varying street patterns and housing density and by clustering housing units, a subdivider can dramatically increase the amount of open and recreational space within a development.

Private land-use controls are exercised by owners through deed restrictions and restrictive covenants. These private restrictions may be enforced by obtaining a court injunction to stop a violator.

Subdivided land sales are regulated on the federal level by the Interstate Land Sales Full Disclosure Act. This law requires that developers engaged in certain interstate land sales or leases register the details of the land with HUD. Developers also must provide prospective purchasers or lessees with property reports containing all essential information about the property in any development that exceeds 25 lots.

RELATED STATE OF TENNESSEE LAWS, RULES, and REGULATIONS

FAQ’s about Zoning Issues

What is the source of zoning authority enjoyed by Tennessee communities?

Through TCA 13-7-101, cities and/or counties in Tennessee receive their zoning authority from the state, and without such authority no zoning ordinances could exist.

Is there a definition of a subdivision?

When appropriate to the context, subdivision relates to the process of resubdividing or to the land or area subdivided. Subdivision generally means the division of a tract or parcel of land into two or more lots, sites, or other divisions requiring new streets or utility construction. Or it could mean any division of less than five acres for the purpose, whether immediate or for the future, of sale or building development, and includes resubdivision.

Who or what regulates construction?

Tennessee has adopted the 1999 National Building Code. However, enforcement of building codes are left to the individual counties. Consequently, enforcement varies widely from county to county.

Any other special regulations?

Tennessee law regulates handicapped housing and manufactured homes.