CHAPTER SEVEN

INTERESTS IN REAL ESTATE

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

When you've finished reading this Chapter, you should be able to:

► identify the kinds of limitations on ownership rights that are imposed by government action and the form of conveyance of property.

► describe the various estates in land and the rights and limitations they convey.

► explain concepts related to encumbrances and water rights.

► distinguish the various types of police powers and how they are exercised.

► define the following key terms: accretion; encroachment; license; appurtenant easement; encumbrance; lien; avulsion; erosion; life estate; condemnation; escheat; littoral rights; deed restrictions; estate in land; party wall; easement; fee simple; police power; easement by; fee simple absolute; prior appropriation; condemnation ; fee simple defeasible; remainder interest; easement by necessity; fee simple determinable; reversionary interest; easement by prescription; freehold estate; riparian rights; future interest; taxation; easement in gross; homestead; eminent domain; leasehold estate.

REAL ESTATE PRACTICE & PRINCIPLES KEY WORD MATCH QUIZ

--- CLICK HERE ---

I would encourage you to take this “Match quiz” now as a pre-chapter challenge to see how many of these key words or phrases you are familiar with. At the end of each chapter I recommend that you take the quiz again to reinforce these important keywords. Each page contains four words or phrases and you need to drag and drop the correct definition into the puzzle key. Each page is considered as a question, but there is no scoring and you can return to each chapter quiz as many times as needed to reinforce your memory.

► WHY LEARN ABOUT... INTERESTS IN REAL ESTATE?

As discussed in Chapter 2, an extensive bundle of rights goes along with owning real estate. However, there are many different interests in real estate that can be acquired, and not all of them convey the entire bundle of legal rights to the owner. Licensees must take great care to ensure that prospective buyers understand exactly what interests a seller wishes to transfer. While only a lawyer can accurately (and legally) identify and interpret legal issues, a savvy licensee will be aware of any potential problems and address them in a timely manner.

► LIMITATIONS ON THE RIGHTS OF OWNERSHIP

Ownership of real estate is not absolute, that is, a landowner's power to control his or her property is subject to other interests. Keep in mind that a landowner's power to control his or her property relates to the landowner having title of the property and the bundle of legal rights that accompanies the title. Even the most complete ownership the law allows is limited by public and private restrictions. These are intended to ensure that one owner's use or enjoyment of his or her property does not interfere with others' use or enjoyment of their property or with the welfare of the general public. Licensees should have a working knowledge of the restrictions that might limit current or future owners. A zoning ordinance that will not allow a doctor's office to coexist with a residence, a condo association bylaw prohibiting resale without board approval, or an easement allowing the neighbors to use the private beach may not only burden today's purchaser but also deter a future buyer.

This Chapter puts the various interests in real estate in perspective—what rights they confer and how use of the ownership may be limited.

► GOVERNMENT POWERS

Individual ownership rights are subject to certain powers, or rights, held by federal, state, and local governments. These limitations on the ownership of real estate are imposed for the general welfare of the community and, therefore, supersede the rights or interests of the individual. Government powers include police power, eminent domain, taxation, and escheat.

Police Power

Every state has the power to enact legislation to preserve order, protect the public health and safety, and promote the general welfare of its citizens. That authority is known as a state's police power. The state's authority is passed on to municipalities and counties through legislation called enabling acts.

Of course, what is identified as being "in the public interest" varies widely from state to state and region to region. Generally, however, a police power is used to enact environmental protection laws, zoning ordinances, and building codes.

Regulations that govern the use, occupancy, size, location, and construction of real estate also fall within the police powers.

Police powers may be used to achieve a community's needs or goals. A city that deems growth to be desirable, for instance, may exercise its police powers to enact laws encouraging the purchase and improvement of land. On the other hand, an area that wishes to retain its current character may enact laws that discourage development and population growth.

Like the rights of ownership, the state's power to regulate land use is not absolute. The laws must be uniform and nondiscriminatory; that is, they may not operate to the advantage or disadvantage of any one particular owner or owners. See Chapter 19 for more on police power.

Eminent Domain

Eminent domain is the right of the government to acquire privately owned real estate for public use. Condemnation is the process by which the government exercises this right, by either judicial or administrative proceedings. The proposed use must be for the public good, just compensation must be paid to the owner, and the rights of the property owner must be protected by due process of law. Public use has been defined very broadly by the courts to include not only public facilities but also property that is no longer fit for use and must be closed or destroyed.

Generally, the states delegate their power of eminent domain to quasi-public bodies and publicly held companies responsible for various facets of public service. For instance, a public housing authority might take privately owned land to build low-income housing; the state's land-clearance commission or redevelopment authority could use the power of eminent domain to make way for urban renewal. If there were no other feasible way to do so, a railway, utility company, or state highway department might acquire farmland to extend a railroad track, bring electricity to a remote new development, or build a highway. Again, all are allowable as long as the purpose contributes to the public good.

Ideally, the public agency and the owner of the property in question agree on compensation through direct negotiation, and the government purchases the property for a price considered fair by the owner. In some cases, the owner may simply dedicate the property to the government as a site for a school, park, library, or another beneficial use. Sometimes, however, the owner's consent can-not be obtained. In those cases, the government agency can initiate condemnation proceedings to acquire the property.

Taxation

Taxation is a charge on real estate to raise funds to meet the public needs of a government.

Although escheat is not actually a limitation on ownership, it is an avenue by which the state may acquire privately owned real or personal property. State laws provide for ownership to transfer, or escheat, to the state when an owner dies leaving no heirs (as defined by the law) and no will that directs how the real estate is to be distributed. In some states, real property escheats to the county where the land is located; in others, it becomes the property of the state. Escheat is intended to prevent property from being ownerless or abandoned.

► ESTATES IN LAND

An estate in land defines the degree, quantity, nature, and extent of an owner's interest in real property. Many types of estates exist. However, not all interests in real estate are estates. To be an estate in land, an interest must allow possession (either now or in the future) and must be measurable by duration. Lesser interests such as easements (discussed later in this Chapter), which allow use but not possession, are not estates.

FOR EXAMPLE Bob owns a movie theater. Bob's ownership interest is an estate because Bob has the right to all the income from the theater, the right to change the theater into a restaurant, the right to tear down the theater and build something else on the land, and the right to sell the theater to someone else—in short, the theater belongs to Bob. When Matt buys a ticket and sits down to watch a movie in Bob's theater, Matt has an interest in the property, but it is not an estate. Matt's interest is limited to the temporary use of a limited part of the theater.

Historically, estates in land have been classified as freehold estates and leasehold estates. The two types of estates are distinguished primarily by their duration.

Freehold estates last for an indeterminable length of time, such as for a lifetime or forever. They include fee simple (also called an indefeasible fee), defeasible fee, and life estates. The first two of these estates continue for an indefinite period and may be passed along to the owner's heirs. A life estate is based on the life-time of a person and ends when that individual dies. Freehold estates are illustrated in Figure 7.1.

Leasehold estates last for a fixed period of time. They include estates for years and estates from period to period. Estates at will and estates at sufferance are also leaseholds, though by their operation they are not generally viewed as being for fixed terms.

Fee Simple Estate

An estate in fee simple (or fee simple absolute) is the highest interest in real estate recognized by law. Fee simple ownership is absolute ownership: The holder is entitled to all rights to the property. It is limited only by public and private restrictions, such as zoning laws and restrictive covenants (discussed in Chapter 19). Because this estate is of unlimited duration, it is said to run forever. Upon the death of its owner, it passes to the owner's heirs or as provided by will. A fee simple estate is also referred to as an estate of inheritance or simply as fee ownership.

Fee simple defeasible. A fee simple defeasible (or defeasible fee) estate is a qualified estate—that is, it is subject to the occurrence or nonoccurrence of some specified event. Two types of defeasible estates exist: those subject to a condition subsequent and those qualified by a special limitation.

A fee simple estate may be qualified by a condition subsequent, which means that the new owner must not perform some action or activity. The former owner retains a right of reentry so that if the condition is broken, the former owner can retake possession of the property through legal action. Conditions in a deed are different from restrictions or covenants because of the grantor's right to reclaim ownership, a right that does not exist under private restrictions.

FOR EXAMPLE A grant of land "on the condition that" there be no consumption of alcohol on the premises is a fee simple subject to a condition subsequent. If alcohol is consumed on the property, the former owner has the right to reacquire full ownership. It will be necessary for the grantor (or the grantor's heirs or successors) to go to court to assert that right, however.

A fee simple estate also may be qualified by a special limitation. The estate ends automatically on the current owner's failure to comply with the limitation. The former owner retains a possibility of reverter. If the limitation is violated, the former owner (or his or her heirs or successors) reacquires full ownership, with no need to reenter the land or go to court. A fee simple with a special limitation is also called a fee simple determinable because it may end automatically. The language used to distinguish a special limitation— the words so long as or while or during—is the key to creating this estate.

The right of entry and possibility of reverter may never take effect. If they do, it will be only at some time in the future. Therefore, each of these rights is considered a future interest.

FOR EXAMPLE A grant of land from an owner to her church "so long as the land is used only for religious purposes" is a fee simple with a special limitation. The church has the full bundle of rights possessed by a property owner, but one of the "sticks" in the bundle—the "control" stick, in this case—has a string attached. If the church ever decides to use the land for a nonreligious purpose, the original owner will, in effect, "yank the string," causing title to revert to him or her (or to his or her heirs or successors).

Life Estate

A life estate is a freehold estate limited in duration to the life of the owner or the life of some other designated person or persons. Unlike other freehold estates, a life estate is not inheritable and cannot be devised. It passes to future owners according to the provisions of the life estate.

A life tenant is entitled to the rights of ownership, that is, the life tenant can enjoy both possession and the ordinary use and profits arising from ownership, just as if the individual were a fee owner. The ownership may be sold, mortgaged, or leased, but it is always subject to the limitation of the life estate.

A life tenant's ownership rights, however, are not absolute. The life tenant may not injure the property, such as by destroying a building or allowing it to deteriorate. In legal terms, this injury is known as waste. Those who will eventually own the property could seek an injunction against the life tenant or sue for damages.

Because the ownership will terminate on the death of the person against whose life the estate is measured, a purchaser, lessee, or lender can be affected. The life tenant can sell, lease, or mortgage only his or her interest— that is, ownership for a lifetime. Because the interest is obviously less desirable than a fee simple estate, the life tenant's rights are limited.

Conventional life estate. A conventional life estate is created intentionally by the owner. It may be established either by deed at the time the ownership is transferred during the owner's life or by a provision of the owner's will after his or her death. The estate is conveyed to an individual who is called the life ten-ant. The life tenant has full enjoyment of the ownership for the duration of his or her life. When the life tenant dies, the estate ends and its ownership passes to another designated individual or returns to the previous owner.

FOR EXAMPLE Alex, who has a fee simple estate in Blackacre, conveys a life estate to Peter for Peter's lifetime. Peter is the life tenant. On Peter's death, the life estate terminates, and Alex once again owns Blackacre. If Peter's life estate had been created by Alex's will, however, subsequent ownership of Blackacre would be determined by the provisions of the will.

Pur autre vie. A life estate also may be based on the lifetime of a person other than the life tenant. This is known as an estate pur autre vie ("for the life of another"). Although a life estate is not considered an estate of inheritance, a life estate pur autre vie provides for inheritance by the life tenant's heirs only until the death of the person against whose life the estate is measured. A life estate pur autre vie is often created for a physically or mentally incapacitated person in the hope of providing an incentive for someone to care for him or her.

FOR EXAMPLE Alex conveys a life estate in Blackacre to Peter as the life tenant for the duration of the life of Dale, Alex's elderly relative. Peter is still the life tenant, but the measuring life is Dale's. On Dale's death, the life estate ends. If Peter should die while Dale is still alive, Peter's heirs may inherit the life estate. However, when Dale dies, the heirs' estate ends.

Remainder and reversion. The fee simple owner who creates a conventional life estate must plan for its future ownership. When the life estate ends, it is replaced by a fee simple estate. The future owner of the fee simple estate may be designated in one of two ways:

1. Remainder interest: The creator of the life estate may name a remainder-man as the person to whom the property will pass when the life estate ends. (Remainderman is the legal term; neither the term remainderperson nor the term remainderwoman is used.)

2. Reversionary interest: The creator of the life estate may choose not to name a remainderman. In that case, the creator will recapture ownership when the life estate ends. The ownership is said to revert to the original owner.

FOR EXAMPLE Alex conveys Blackacre to Peter for Peter's lifetime and designates Rick to be the remainderman. While Peter is still alive, Rick owns a remainder interest, which is a nonpossessory estate; that is, Rick does not possess the property but has an interest in it nonetheless. This is a future interest in the fee simple estate. When Peter dies, Rick automatically becomes the fee simple owner.

On the other hand, Alex may convey a life estate in Blackacre to Peter during Peter's life. On Peter's death, ownership of Blackacre reverts to Alex. Alex has retained a reversionary interest (also a nonpossessory estate). Alex has a future interest in the ownership and may reclaim the fee simple estate when Peter dies. If Alex dies before Peter, Alex's heirs (or other individuals specified in Alex's will) will assume ownership of Blackacre when Peter dies.

Legal life estate. A legal life estate is not created voluntarily by an owner. Rather, it is a form of life estate established by state law. It becomes effective automatically when certain events occur. Dower, curtesy, and homestead are the legal life estates currently used in some states.

Dower and curtesy provide the nonowning spouse with a means of support after' the death of the owning spouse. Dower is the life estate that a wife has in the real estate of her deceased husband. Curtesy is an identical interest that a husband has in the real estate of his deceased wife. (In some states, dower and curtesy are referred to collectively as either dower or curtesy.)

Dower and curtesy provide that the nonowning spouse has a right to a one-half or one-third interest in the real estate for the rest of his or her life, even if the owning spouse wills the estate to others. Because a nonowning spouse might claim an interest in the future, both spouses may have to sign the proper documents when real estate is conveyed. The signature of the nonowning spouse would be needed to release any potential common-law interests in the property being transferred.

Like Tennessee, most states have abolished the common-law concepts of dower and curtesy in favor of the Uniform Probate Code (UPC). The UPC gives the surviving spouse a right to an elective share on the death of the other spouse. Community property states never used dower and curtesy. (Community property is discussed in Chapter 8.)

2010 Tennessee Code Title 31 - Descent And Distribution Chapter 2 - Intestate Succession

31-2-102 - Dower and curtesy abolished.

Dower and curtesy, as formerly known, are abolished. This section shall neither abridge nor affect rights that have vested before April 1, 1977.

[Acts 1976, ch. 529, § 1; 1977, ch. 25, §§ 4, 5; T.C.A., § 31-202.]

A homestead is a legal life estate in real estate occupied as the family home. In effect, the home (or at least some part of it) is protected from creditors during the occupant's lifetime. In states that have homestead exemption laws, a portion of the area or value of the property occupied as the family home is exempt from certain judgments for debts such as charge accounts and personal loans. The homestead is not protected from real estate taxes levied against the property or

a mortgage for the purchase or cost of improvements, that is;- if the debt is secured-by the property, the property cannot be exempt from a judgment on that debt.

In some states, all that is required to establish a homestead is for the head of a household (sometimes a single person) to own or lease the premises occupied by the family as a residence. In other states, the family is required by statute to file a notice. A family can have only one homestead at any given time.

How does the homestead exemption actually work?

In most states, the home-stead exemption merely reserves a certain amount of money for the family in the event of a court sale. In a few states, however, the entire homestead is protected from sale altogether. Once the sale occurs, any debts secured by the home (a mortgage, unpaid taxes, or mechanics' liens, for instance) will be paid from the proceeds. Then the family will receive the amount reserved by the homestead exemption. Finally, whatever remains will be applied to the family's unsecured debts.

FOR EXAMPLE Greenacre is Tim's homestead. In Tim's state, the homestead exemption is $25,000. At a court-ordered sale, the property is purchased for $60,000. First, Tim's remaining $15,000 mortgage balance is paid; then Tim receives $25,000. The remaining $20,000 is applied to Tim's unsecured debts.

Of course, no sale would be ordered if the court could determine that nothing would remain from the proceeds for the creditors. If Greenacre could not be expected to bring more than $40,000, the priority of the mortgage lien and homestead exemption would make a sale pointless.

► ENCUMBRANCES

An encumbrance is a claim, charge, or liability that attaches to real estate. An encumbrance does not have a possessory interest in real property; it is not an estate. Simply put, an encumbrance is a right or an interest held by someone other than the fee owner of the property that affects title to real estate. An encumbrance may lessen the value or obstruct the use of the property, but it does not necessarily prevent a transfer of title.

Encumbrances may be divided into the following two general classifications:

1. Liens (usually monetary charges) and

2. Encumbrances such as restrictions, easements, and encroachments that affect the condition or use of the property.

Liens

A lien is a charge against property that provides security for a debt or an obligation of the property owner. If the obligation is not repaid, the lienholder is entitled to have the debt satisfied from the proceeds of a court-ordered or forced sale of the debtor's property. Real estate taxes, mortgages and trust deeds, judgments, and mechanics' liens all represent possible liens against an owner's real estate. Liens are discussed in detail in Chapter 10.

Deed Restrictions

Deed restrictions, also referred to as covenants, conditions, and restrictions, or CC&Rs, are private agreements that affect the use of land. They may be imposed by an owner of real estate and included in the seller's deed to the buyer. Typically, however, restrictive covenants are imposed by a developer or subdivider to maintain specific standards in a subdivision. Such restrictive covenants are listed in the original development plans for the subdivision filed in the public record. Deed restrictions are discussed further in Chapter 19.

Easements

An easement is the right to use the land of another for a particular purpose. An easement may exist in any portion of the real estate, including the airspace above or a right-of-way across the land.

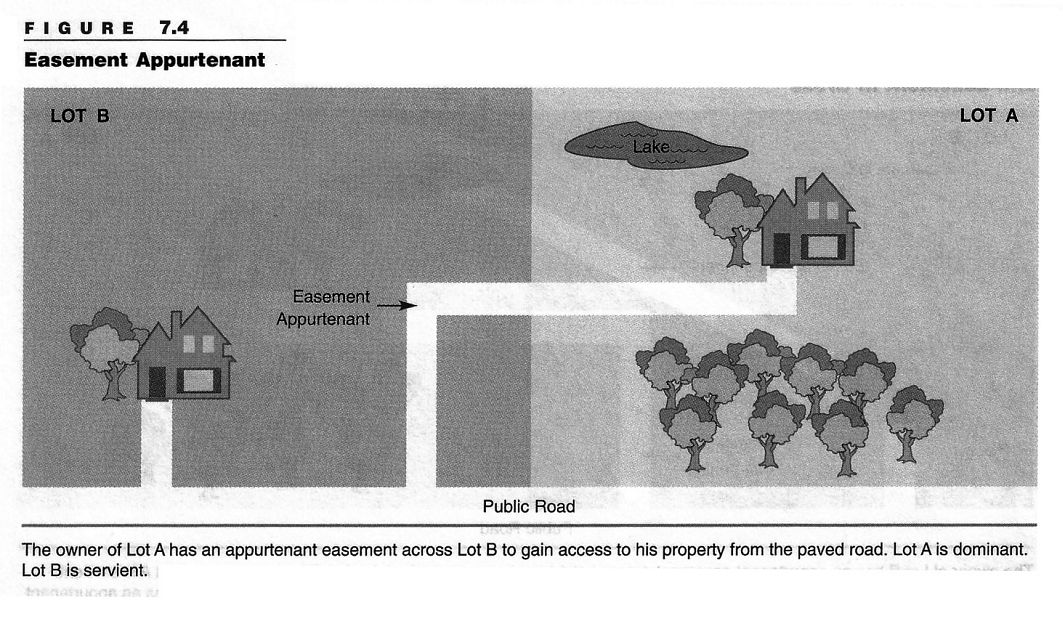

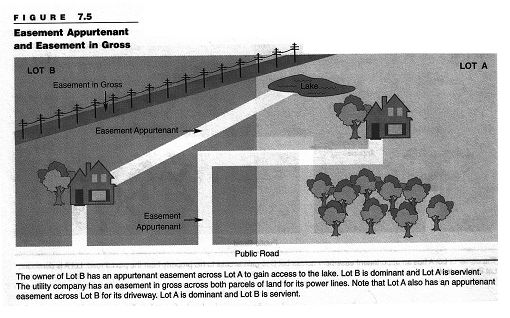

An appurtenant easement is annexed to the ownership of one parcel and allows this owner the use of a neighbor's land. For an appurtenant easement to exist, two adjacent parcels of land must be owned by two different parties. The parcel over which the easement runs is known as the servient tenement; the neighboring parcel that benefits is known as the dominant tenement. (See Figure 7.4 and Figure 7.5.)